Socrates probably did not ask that question. But if he were a Python developer, I bet he would ask, What does it mean to be Pythonic?

@billah_tishad on X

Demistifying the Term Pythonic

Modasser Billah

Backend Lead, Doist

🗓️ PyCon MY, 2025

I'm Modasser Billah and today I'll share with you my journey through the many different ideas of what Pythonic means.

But first a little bit about me:

I am from a small town in Bangladesh called Comilla. It’s about 2 hours ride from the capital Dhaka where I currenlty live.

I work as a Backend Lead @ Doist

Doist is fully remote and one of the pioneers in remote and async work culture.

We have 2 products Todoist and Twist. Todoist is a task and project manager that brings clarity and efficiency to millions of people and teams. And Twist is an asynchronous-first collaboration and communication app for teams.

We do not have any offices and you can work with us from anywhere in the world. If that piques your interest, keep an eye on our careers page.

Our backends are built in Python.

Our backends are built in Python.

So the term Pythonic pops up every now and then in my mind.

I'm no philosopher myself so I did not really think about it when I first heard the term.

To be honest, I was more like this when I started out. So you see I had more existential questions to think about.

But it kept popping up, in Stack overflow, in code reviews, in blog posts. Again, I'm no Socrates, I wasn't really looking to explore. I was happy with answers handed over to me. And if you turn to the internet for answers, you will probably find too many.

🎬 1: List Comprehensions are Pythonic

So the first answer I adopted was...

🎬 1: List Comprehensions are Pythonic

🤓 For loops are so unPythonic

Use list comprehensions

Or any comprehensions really

Which in turn made me a proponent of...For loops are so unPythonic. Use list comprehensions Or any comprehensions really

It is a stupid simplification but my conclusion was to use clever list comprehensions that Java people would not understand. Not to offend Java programmers, it's just that I started with Java and then came over to Python. So, Java was the reference point in my head.

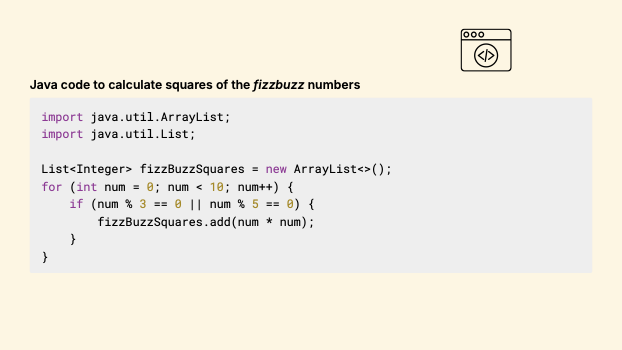

Java code to calculate squares of the fizzbuzz numbers

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

List<Integer> fizzBuzzSquares = new ArrayList<>();

for (int num = 0; num < 10; num++) {

if (num % 3 == 0 || num % 5 == 0) {

fizzBuzzSquares.add(num * num);

}

}

Look at this java code to calculate squares of the fizz buzz numbers:

A note about code in the slides: the code snippets in the slides are there to drive a point home. So, don’t stress too much on reading it line by line, just follow along with me.

Okay back to the code...

so this is a java code snippet to calculate squares of the fizz buzz numbers, numbers that are divisible by 3 or 5 or both

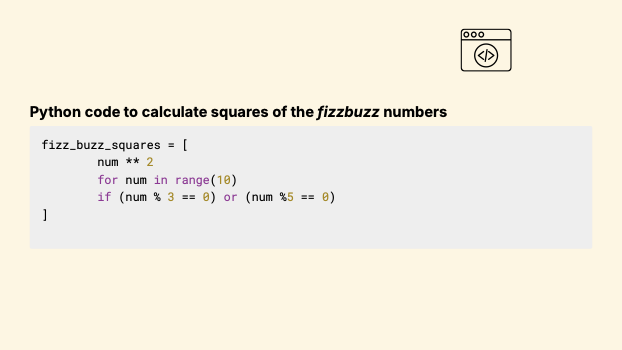

Python code to calculate squares of the fizzbuzz numbers

fizz_buzz_squares = [

num ** 2

for num in range(10)

if (num % 3 == 0) or (num %5 == 0)

]

Now let’s look at the same code in Python:

No imports, no loop counters, just pure Pythonic bliss!

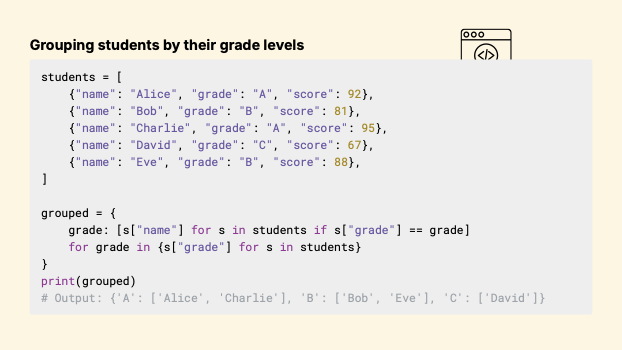

Grouping students by their grade levels

students = [

{"name": "Alice", "grade": "A", "score": 92},

{"name": "Bob", "grade": "B", "score": 81},

{"name": "Charlie", "grade": "A", "score": 95},

{"name": "David", "grade": "C", "score": 67},

{"name": "Eve", "grade": "B", "score": 88},

]

grouped = {

grade: [s["name"] for s in students if s["grade"] == grade]

for grade in {s["grade"] for s in students}

}

print(grouped)

# Output: {'A': ['Alice', 'Charlie'], 'B': ['Bob', 'Eve'], 'C': ['David']}

So there was a time when my first attempt to solve any problem was to think, how can I use a comprehension here?

I got obsessed with comprehensions. Lists, dicts, sets you name it.

For example, let’s assume we have a list of student records. We want to group students by their grades.

This is a working solution with multiple comprehensions bundled together.

Slick, but I had to read it a few times to get it. It uses a dict comprehension. And inside the dict it uses two more comprehensions for the keys and the values.

🎬 2: Clever one-liners are Pythonic

That obsession with comprehensions also brought over its smart cousin..

🎬 2: Clever one-liners are Pythonic

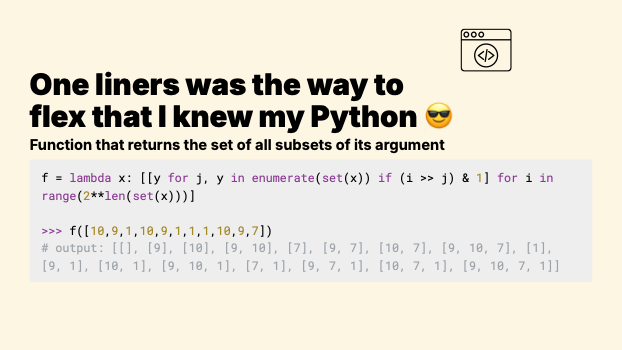

One liners was the way to flex that I knew my Python 😎

Function that returns the set of all subsets of its argument

f = lambda x: [[y for j, y in enumerate(set(x)) if (i >> j) & 1] for i in range(2**len(set(x)))]

>>> f([10,9,1,10,9,1,1,1,10,9,7])

# output: [[], [9], [10], [9, 10], [7], [9, 7], [10, 7], [9, 10, 7], [1], [9, 1], [10, 1], [9, 10, 1], [7, 1], [9, 7, 1], [10, 7, 1], [9, 10, 7, 1]]

One liners was the way to flex that I knew my Python 😎

This is a Function that returns the set of all subsets of its argument. Hardly readable yet works.

The more you could do with a smart one-liner, the better Pythonista you are...

Or so I thought!

There's almost a community around one-liners in Python.

And in my defence, it's not just me. There's almost a community around one-liners in Python.

There's a book, there's a wiki and so much more. I'm totally cool with it, it's fun and a learning experience.

But how far do we take it? At what point does it stop being Pythonic?

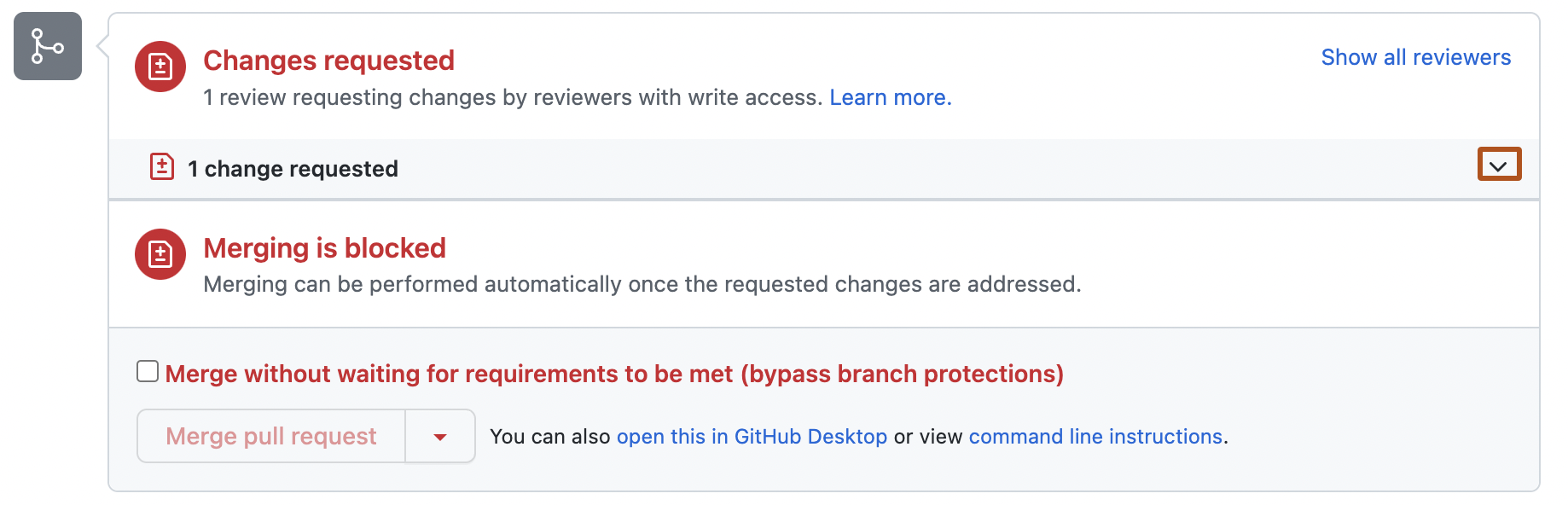

💔 Your code is not Pythonic

That day eventually came. I got a code review that told me my code is concise but it is hardly readable and hence it was not Pythonic!

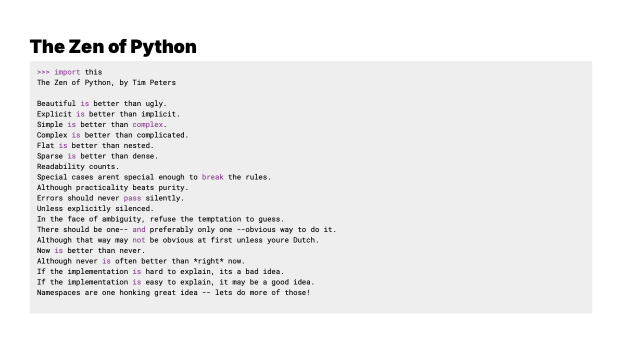

🎬 3: The Zen of Python

Every heart-break opens new doors. Now It was my turn to be more spiritual in my Python journey...

And thus entered the stage, the zen of Python.

The Zen of Python

>>> import this

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases arent special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless youre Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, its a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- lets do more of those!

The Zen of Python is a collection of 19 guiding principles for writing computer programs in Python. These were later standardised in PEP 20. If you run import this from a python shell, you’ll see it.

Zen of Python are Aphorisms that came with wisdom. But I barely had the depth to appreciate it.

Simple is better than complex.

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Now is better than never.

My apologies to Tim Peters. But I can't remove the image of Master Oogway from my head when I read the zen of Python...

You’re a wise man Tim! Oogway would be proud.

But like Po, who had no clue in the beginning what master Oogway was saying, I did not know any better either.

I was merely parroting the wisdom.

There were a few more phases of - oh this is Pythonic, that is Pythonic without much thought.

Think PEP-8, functional programming and so on. Eventually my hairs started turning grey and one day I finally asked myself, like a philosopher, what IS Pythonic?

Socrates used the tool of questioning to strip away all preconceived notions and dogmas surrounding one’s cherished beliefs.

Credit: More To That by Lawrence Yeo

Today I will try to apply the Socratic method to search for an answer. The Socratic method uses the tool of questioning to chip away at our fuzzy understandings and implicit assumptions. And thus, it exposes the gaps in our understanding.

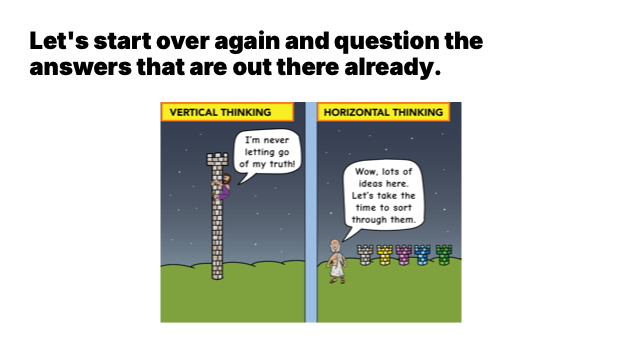

Let's start over again and question the answers that are out there already.

Let's start over again and question the answers that are out there already. When we grab an answer and stick to it, it makes it hard for us be open to different opinions.

When we start from a place of uncertainty, we give ourselves a better chance of getting closer to reality and give all options on the ground a fair chance.

What does it mean to be anything❓

First, let's start from a more generalised starting point. What does it mean to be anything at all?

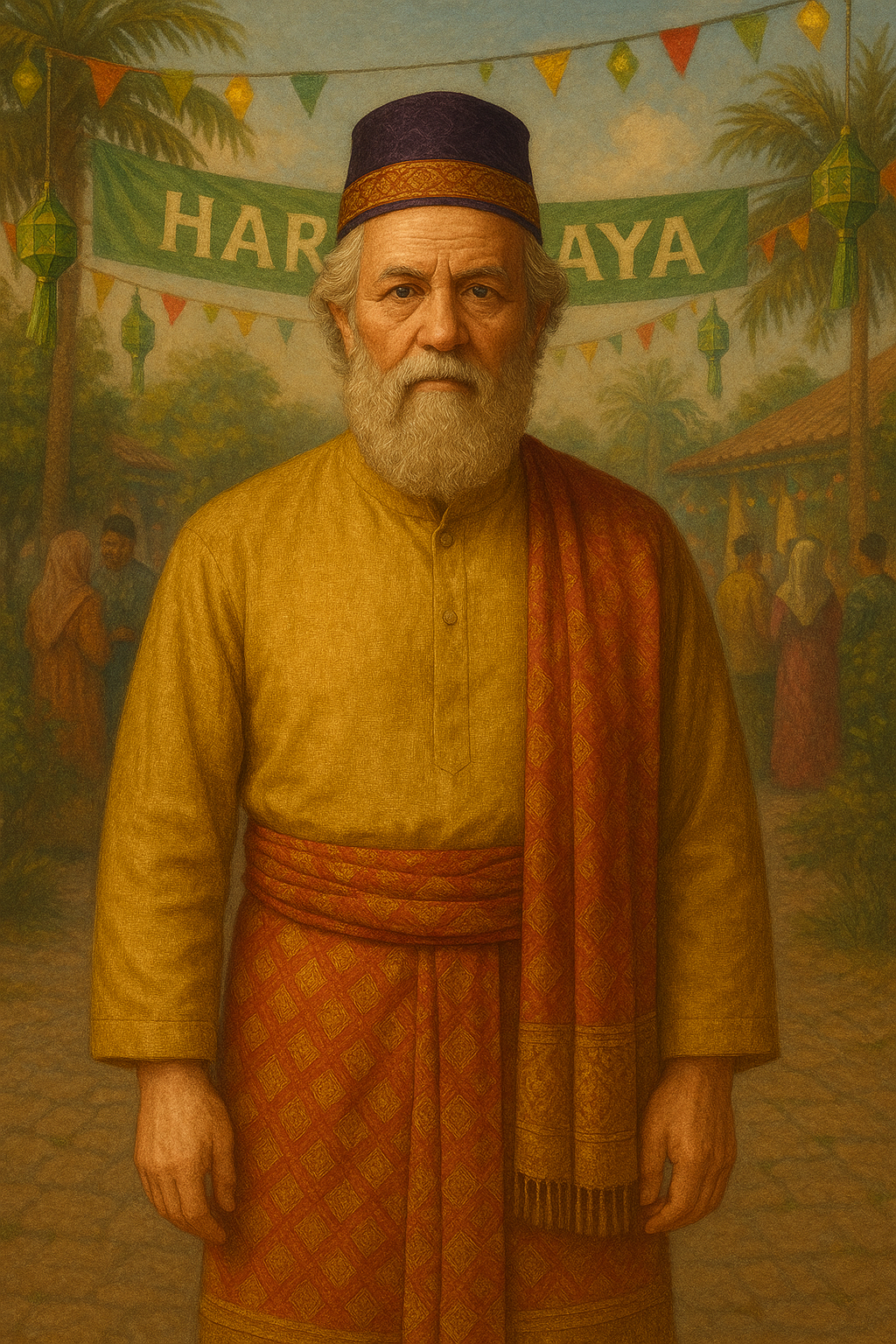

What does it mean to be Malaysian❓

What does it mean to be Malaysian, for example?

.png)

If Socrates ate Nasi Lemak, would he become Malaysian?

If someone eats Malaysian food, would he become Malaysian? If Socrates ate Nasi Lemak, would he become Malaysian?

If Socrates wore Baju Melayu, would he become Malaysian?

If someone dressed like Malaysian people, would he become Malaysian? Taking Socrates with us through the journey, if he wore Baju melayu, would he become Malaysian?

Probably not but food and dresses are significant aspects of a culture or nation. Although, I’m sure you'd agree there's more to it in being Malaysian than just the cuisine and clothing. And That gives us a good heuristic.

Learning from our analogy, we can say that Pythonic can be many things that combine to form the soul of it.

But superficially adopting one or two of those does not give us the full picture.

So, like food and clothing, list comprehensions and one-liners are very much part of the zeitgeist of being Pythonic but surely, there's more to it.

Why are comprehensions Pythonic?

So if Socrates the Python developer asked me, what is Pythonic and I replied, list comprehensions are Pythonic.

He'd probably ask, Why is that Pythonic?

Which begs the question...

Why is anything Pythonic❓

Which begs the question...

Why is anything Pythonic❓

.png)

Someone posted this on Stack Overflow:

And there are some angry people out there who do not like this question at all...

Someone posted this on Stack Overflow:

First and foremost - Pythonic is a term that needs to disappear, preferably with everyone who uses it. It doesn't mean anything and it's used by people who can't use reason to justify anything, so they need a term to justify their nonsense.

Wow, I guess I should end my talk here 😅

But languages and terms chart their own course. The wonderful organizers of Pycon Malaysia accepted my talk on this topic. Pythonic is still very much alive as a term. So, our journey continues..

Javascriptic?

Java’s Cryptic?

Of course, it is!

And javascript, too!

I guess the word Pythonic was easy on the tongue so it became a thing. We do not hear the same about other languages, like Go-ic or JavaScriptic. Although I must admit, Javascript is cryptic.

🎬 4: Pythonic -> Idiomatic Python

Anyway, What we do come across in other languages, is idiomatic. And people say that a lot about Python as well. It is generally the immediate answer to many of the Why's. Why is this Pythonic? Because it is idiomatic!

So, we have a new answer to our quest...

Pythonic means idiomatic Python

As a non-native English speaker, I did not grasp what idiomatic means when it was first thrown at me in a programming language context. So understanding this expression of Idiomatic is key.

🗣️ A Detour: Idioms in Spoken Language

Now before we ask what is Idiomatic Python, let's go in full Socrates mode, and first ask what is idiomatic?

Every language has its idioms. In English, if your friend has a football match coming up and you tell him, Break a leg!

NO! NOT LITERALLY!!

You're not asking him to be Sergio Ramos and literally send someone to the hospital. You're simply wishing him good luck.

But if you are a non-native speaker and did not come across this expression before, you'd probably be confused.

💡 Idioms carry shared meaning that can’t be translated literally.

Idioms carry shared meaning that can’t be translated literally. Python has idioms too — expressions that *just *make sense in the Python world.

An "idiom" is a phrase or expression whose meaning cannot be understood literally from the meanings of the individual words in it. Instead, idioms have a figurative or symbolic meaning that is recognized by native speakers and is unique to each language.

And therein lies the magic of idioms. Idioms have a figurative meaning. Native speakers share the understanding organically. But if you're an outsider it may seem counter intuitive, even confusing!

What is Idiomatic Python❓

Now that we have a bit more clarity about what idiomatic is, let's go back to idiomatic Python.

List comprehensions are Pythonic because it is idiomatic Python. But what is idiomatic Python and are list comps idiomatic?

The coat of arms of Malaysia

Source: Wikipedia

Going back to the analogy of being Malaysian. The meaning of being Malaysian comes from the rich history, heritage, culture and traditions of the people of Malaysia and how the nation came together. The coat of arms is a good snapshot of it because it tries to capture all the different aspects that bring together a nation.

Similarly, the idiomatic understanding of Python springs forth from how the language was designed, how it evolved and how Pythonistas use it and expect it to be used.

The Coat of Arms for Python

Foundation of Idiomatic Python: __dunder__ methods

I present my argument to you that, Dunder methods is the foundation of idiomatic Python.

The gateway to the heart of Python are the dunder methods.

The weird methods in Python classes that have double underscores on both sides. The double underscore is shortened as dunder in Pythonista lingo. In a way the term dunder is also a Python idiom. You probably won’t hear it anywhere else. No one would understand what it means outside the Python community. And that right there, is what an idiom is.

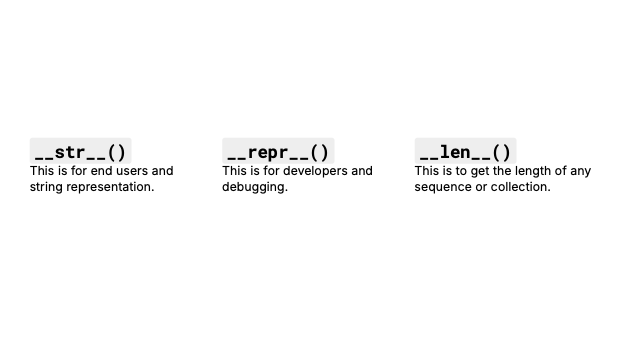

__str__()

This is for end users and string representation.

__repr__()

This is for developers and debugging.

__len__()

This is to get the length of any sequence or collection.

You have probably seen some of these methods already, may be even wrote some...

dunder string is used for string representation. dunder len is used for getting the length of a list and so on.

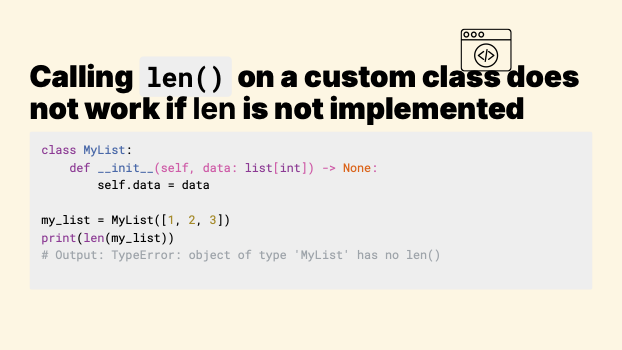

Calling len() on a custom class does not work if len is not implemented

class MyList:

def __init__(self, data: list[int]) -> None:

self.data = data

my_list = MyList([1, 2, 3])

print(len(my_list))

# Output: TypeError: object of type 'MyList' has no len()

But here's the magic, if we write a custom object and call len on it, it doesn’t work if we don’t write a dunder len for it.

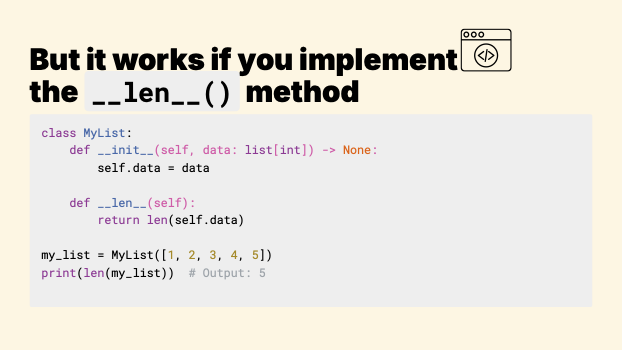

But it works if you implement the __len__() method

class MyList:

def __init__(self, data: list[int]) -> None:

self.data = data

def __len__(self):

return len(self.data)

my_list = MyList([1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

print(len(my_list)) # Output: 5

But if you give it a dunder len method, the len() function will work with our custom object, too!

”By implementing special methods, your objects can behave like the built-in types, enabling the expressive coding style the community considers Pythonic”

🖋️ Luciano Ramalho, Fluent Python

Luciano Ramalho, the author of Fluent Python makes the connection between dunder methods and Pythonic:

”By implementing special methods, your objects can behave like the built-in types, enabling the expressive coding style the community considers Pythonic

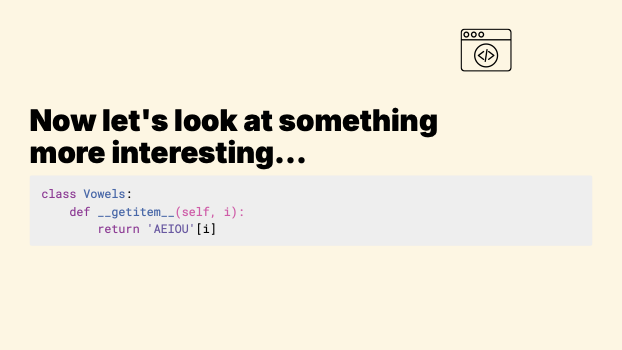

Now let's look at something more interesting...

class Vowels:

def __getitem__(self, i):

return 'AEIOU'[i]

Now let's look at something more interesting...Here we define a class Vowels and it only has one method in it. Pretty simple, right?

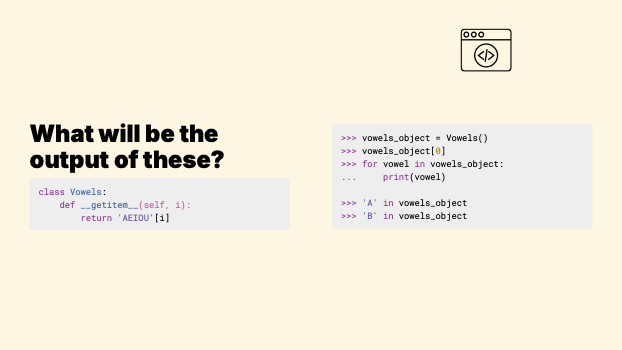

What will be the output of these?

class Vowels:

def __getitem__(self, i):

return 'AEIOU'[i]

>>> vowels_object = Vowels()

>>> vowels_object[0]

>>> for vowel in vowels_object:

... print(vowel)

>>> 'A' in vowels_object

>>> 'B' in vowels_object

Now let's try to guess the output of these, here we try to access an instance of the vowels object using index, then we try to loop through it and then we try some membership checks for characters a and b.

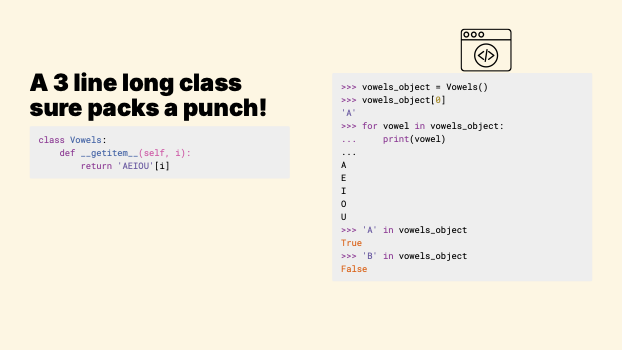

A 3 line long class sure packs a punch!

class Vowels:

def __getitem__(self, i):

return 'AEIOU'[i]

>>> vowels_object = Vowels()

>>> vowels_object[0]

'A'

>>> for vowel in vowels_object:

... print(vowel)

...

A

E

I

O

U

>>> 'A' in vowels_object

True

>>> 'B' in vowels_object

False

Wow, no errors. Looks like the Vowels class supports all of these operations! A 3 line long class sure packs a punch!

Our Vowels class now supports:

- Access via index

- Iteration like a list using

for x in Ysyntax - Membership checks via

x in Ysyntax

class Vowels:

def __getitem__(self, i):

return 'AEIOU'[i]

>>> vowels_object = Vowels()

>>> vowels_object[0]

'A'

>>> for vowel in vowels_object:

... print(vowel)

...

A

E

I

O

U

>>> 'A' in vowels_object

True

>>> 'B' in vowels_object

False

So, we are onto something here. We wrote a 3 liner class but it now supports access via index like lists, it supports iteration and membership checks!

It is! But you can be in on it, too.

Now it is fair to ask...

Is this magic?

The beauty of the design of the Python language is that it shares all the magic with us. Not just what it does, but also a way to let us leverage that magic.

We will go back to our Vowels class later after we have unpacked this magic.

💡 Dunder methods are formally called Special Methods

So dunder methods seem to have some special powers in Python. And rightly so, because...

Dunder methods are formally called Special Methods

We will focus on how it is foundational to Python and hence, Pythonic code.

"The first thing to know about special methods is that they are meant to be called by the Python interpreter and not by you. You don't write my_object.__len__(). You write len(my_object)."

🖋️ Fluent Python, Luciano Ramalho

We go back to the Python Oracle Luciano Ramalho for guidance...

He writes in Fluent Python: "The first thing to know about special methods is that they are meant to be called by the Python interpreter and not by you. You don't write my_object.__len__(). You write len(my_object)."*

Why are special methods special ❓

Okay, so special methods are a big deal. But we more or less know that already. We use them every day. But why are they so special? And how does it work if I define it for one of my classes?

Everything in Python is an object.

But what does that mean?

The answer starts with a cliche...

Everything in Python is an object.

"Objects are Python’s abstraction for data."

Data Model, Official Python Documentation

And the definition of that abstraction is the Python data model.

Lists, Classes, Functions -- everything is an object in Python. The official python documentation says,

"Objects are Python’s abstraction for data."

And the definition of that abstraction is the Python data model.

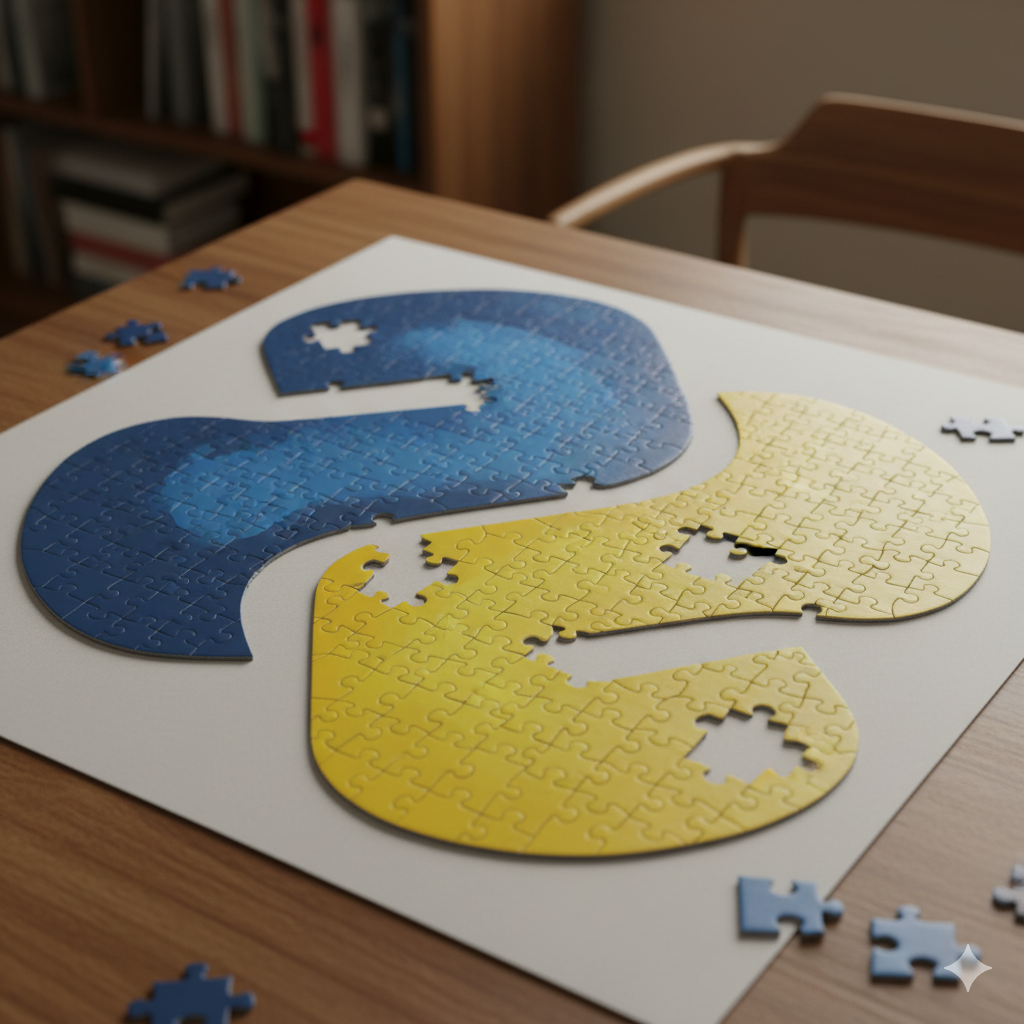

🧩 Enter the Python Data Model

So now the Python data model enters the scene. The official docs have a detailed page on it. Almost all Python books have dedicated chapters on it.

The data model defines how objects:

- Behave with built-ins and syntax

- Interact with the interpreter

- Participate in the ecosystem through

protocolsanddunders

The data model defines how objects:

- Behave with built-ins and syntax

- Interact with the interpreter

- Participate in the ecosystem through

protocolsanddunders

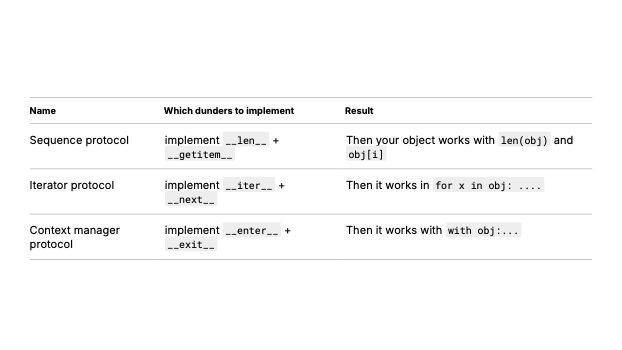

| Name | Which dunders to implement | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence protocol | implement __len__ + __getitem__ |

Then your object works with len(obj) and obj[i] |

| Iterator protocol | implement __iter__ + __next__ |

Then it works in for x in obj: .... |

| Context manager protocol | implement __enter__ + __exit__ |

Then it works with with obj:... |

So, if you want list like behaviour, you implement a set of dunders.

If you want loops and comps, you implement another set of dunders.

and so on...

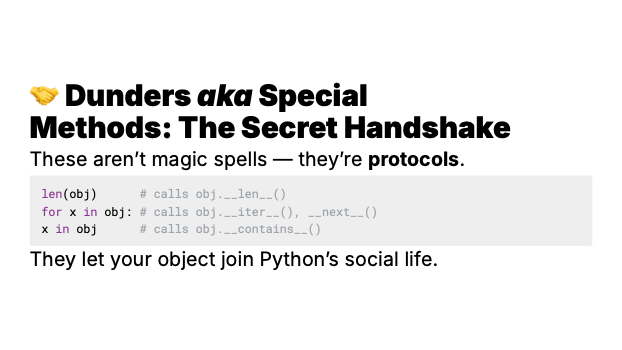

🤝 Dunders aka Special Methods: The Secret Handshake

These aren’t magic spells — they’re protocols.

len(obj) # calls obj.__len__()

for x in obj: # calls obj.__iter__(), __next__()

x in obj # calls obj.__contains__()

They let your object join Python’s social life.

len calls dunder len, for x in obj syntax calls dunder iter, membership checks call dunder contains. So these aren’t magic spells, these are just pre-defined protocols.

They let your object join Python’s social life. Your classes can now hang out with the built-in types and feel like they belong!

.png)

If you're still in the Socratic mood, you probably noticed that I sneaked in a new term, protocols. So, the next question we ask is...

What's a protocol?

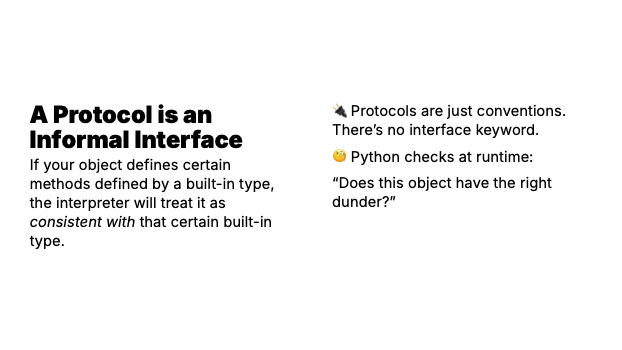

A Protocol is an Informal Interface

If your object defines certain methods defined by a built-in type, the interpreter will treat it as consistent with that certain built-in type.

🔌 Protocols are just conventions. There’s no interface keyword.

🧐 Python checks at runtime:

“Does this object have the right dunder?”

A Protocol is an Informal Interface. Informal because there is no inheritance and Python does not have interfaces at all.

If your object defines certain methods defined by a built-in type, the interpreter will treat it as consistent with that certain built-in type. Python checks at runtime:

“Does this object have the right dunder?” if it does, it stamps it consistent-with and treats it like a native.

Okay, so dunders are the tool we use to implement protocols.

A bundle of dunders form a protocol. The Python data model defines these bundles for various protocols.

So this gives us a good overview of dunders and protocols and how they fit together in the puzzle.

But how are they really connected? How does Python make that connection?

Python under the hood: a sneak peek

To find the connection, we’ll peek under the hood of how Python works.

We won’t go deep into Python internals but let’s try to build a simple mental model that can help us connect the dots.

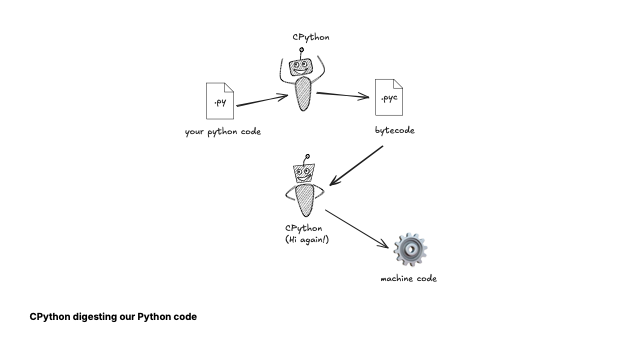

Python is powered by CPython

CPython is the default and official implementation of Python. Which, as the name suggests, is written in C. When we install Python from python.org, we’re actually installing CPython.

CPython digesting our Python code

When we run Python code, it’s actually

CPython doing the heavy lifting.

CPython first turns our code into bytecode. These are the pesky .pyc files that show up in your editor and if you don’t gitignore them, they’ll show up in your repo, too.

The bytecode is then executed line by line by the interpreter, which is also part of the CPython implementation.

This is the step where CPython uses 2 special agents to make sense of the bytecode

Enter PyObject & PyTypeObject

The CPython interpreter uses the PyObject and PyTypeObject structures as core components for managing all Python objects and their behaviour.

All Python constructs are managed using these 2 objects or structs in CPython under the hood.

PyObject is the Brain

Courtesy: Pinky and the Brain cartoon

When we say everything in Python is an object, it fundamentally comes down to this tracking object or c struct pyobject. Which is like the brain of every object in Python

This PyObject is small and mainly keeps track of 2 things:

- a reference count and a pointer to the object type

Which brings us to the other object...

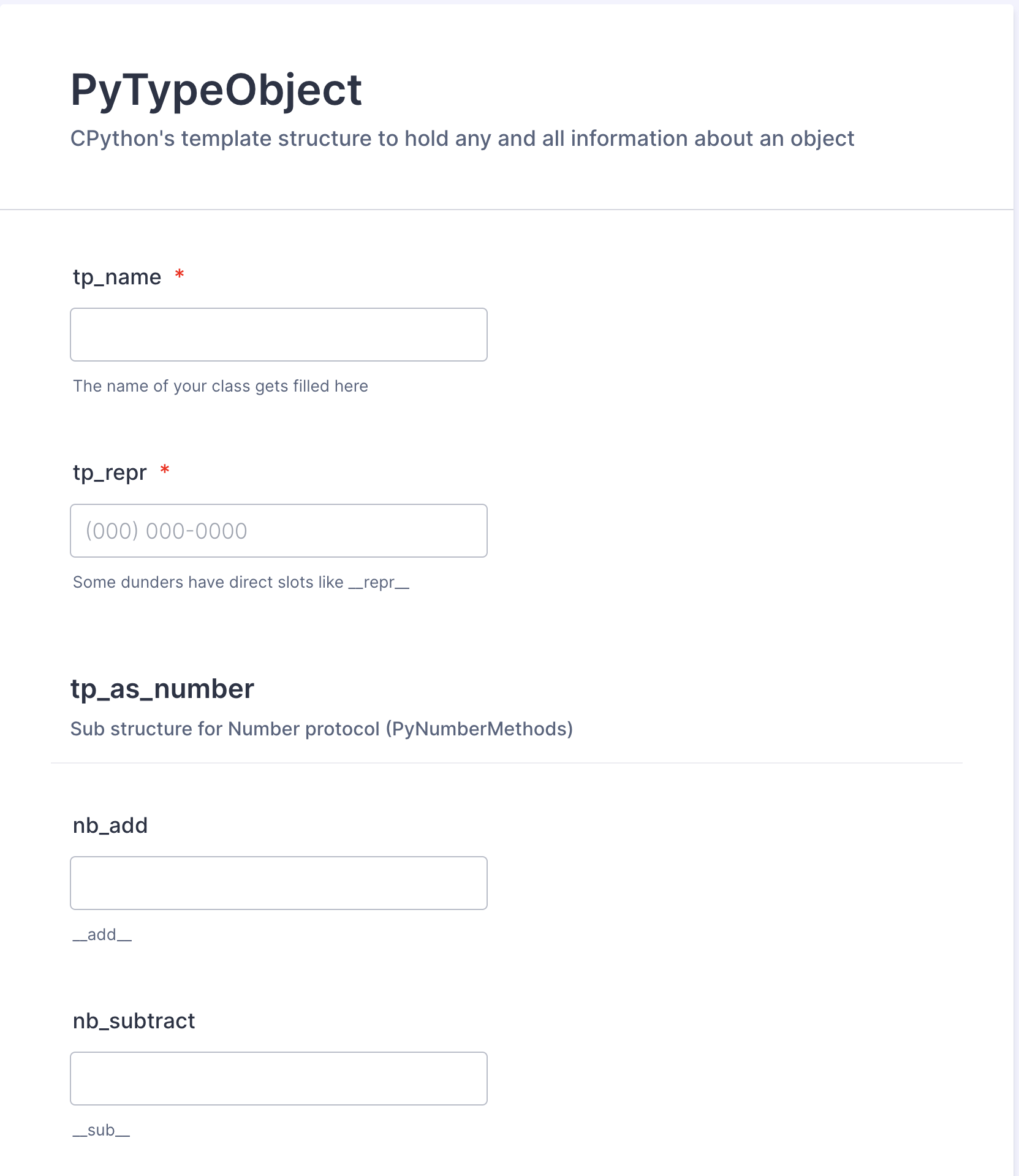

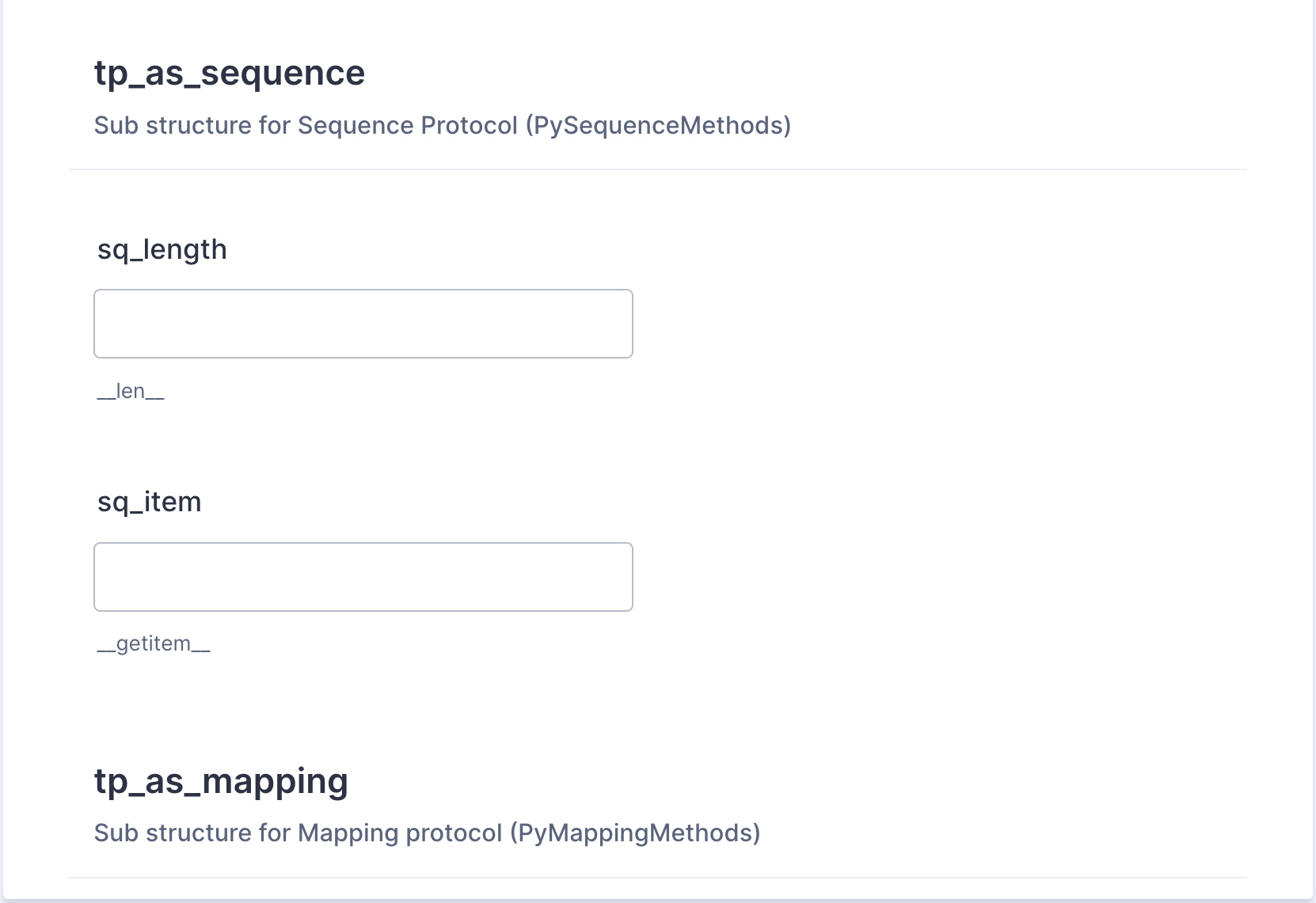

PyTypeObject: the Registry of Everything

The brain, PyObject holds a reference to a PyTypeObject. This tells CPython about the nature of the object.

PyTypeObject is like this huge form that has a lot of fields in it. It has fields (or slots) for every thing. Some are basic and some are divided into sections.

So when the object is compiled for the first time into bytecode, it looks at the class declaration and fills up the fields in the form that are relevant.

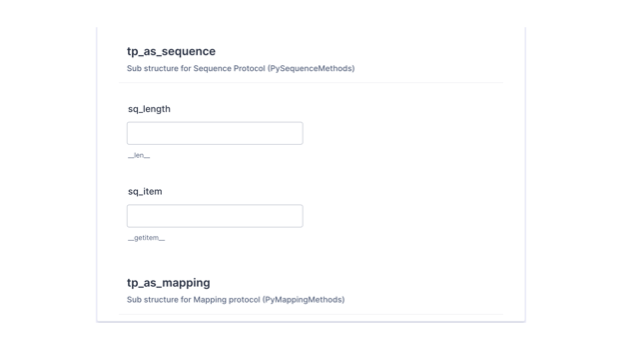

Think of PyTypeObject as a Huge Form

So, it looks at the class name and fills up the slot tp_name.

If it finds a dunder repr, it puts a pointer to that method call into the tp_repr slot.

For protocols it has dedicated sections. There’s a tp_as_sequence slot that points to a PySequenceMethods sub structure, which includes a sq_length slot.

When you add a dunder len, Cpython fills that slot for your class’ PyTypeObject. During execution it finds that tp_as_sequence exists, so it treats your class like a sequence.

And that’s how dunders and protocols run the deep state of the Python world.

🦆 Quacking like a duck is all you need to be a duck in the Python world. No duck parents needed.

If you define certain methods, Python recognises your class as having certain behaviours.

If a duck quacks and you mimic the duck and quack, Python will assume you’re a duck, too.

And python tries really hard to make it work for you. Remember our Vowels class? We did not add __iter__ or __contains__ there, only __getitem__ but it still worked!

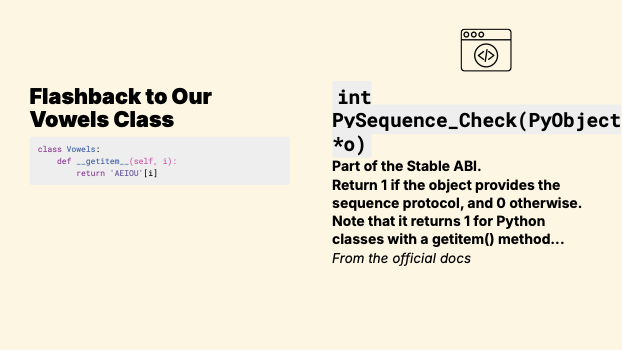

Flashback to Our Vowels Class

class Vowels:

def __getitem__(self, i):

return 'AEIOU'[i]

int PySequence_Check(PyObject *o)

Part of the Stable ABI.

Return 1 if the object provides the sequence protocol, and 0 otherwise. Note that it returns 1 for Python classes with a getitem() method...

From the official docs

So for, loops and membership checks, Python first looks for dunder iter and contains methods. If it finds those, it supports for x in seq style operations.

But if it doesn't find these, it still gives it another honest try. Now it looks for a dunder getitem. If it finds getitem, it uses that to fetch elements in the object one by one using index access. Similarly, it does a full scan of the elements for the membership check.

So as long as relevant fields get filled up in the pytype object, Python will treat your class accordingly.

Back to Idiomatic Python

Now we have a meme based mental model on how Python works under the hood. Let’s get back to idiomatic Python again.

Python idioms are powered by protocols.

So now the dots are connected. dunder methods power many behaviors in built-in types. And protocols are the social contract that allows dunders to provide this privilege. If we implement dunders, we can enjoy those behaviors, too. That’s answers the how.

List comps or idiomatic Python for loops are basically syntactic sugar for these protocols. When you write for x in Y, Python basically reaches out to __iter__ inside Y.

Python protocols are powered by slots in PyTypeObject.

Python protocols are powered by slots in PyTypeObject.

This is why leveraging protocols gives our classes the same powers. So we got the why as well.

User-defined objects work the same way as built-ins if they honour the protocol.

-> A numpy.ndarray implements __add__, so a+b does vectorized addition.

-> A pandas.DataFrame implements __getitem__, so df["col"] works like dictionary access.

We have many awesome libraries that leverage this to create Pythonic libraries that feel native and built-in like...

A numpy.ndarray implements __add__, so a+b does vectorized addition.

A pandas.DataFrame implements __getitem__, so accessing a dataframe column works like dictionary access.

We've come a long way!

Wow, we have come a long way from comprehensions and one-liners!

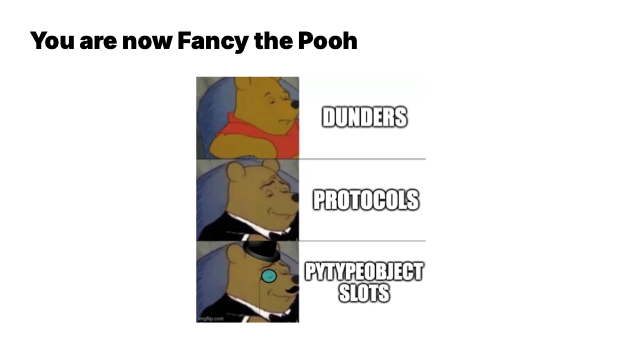

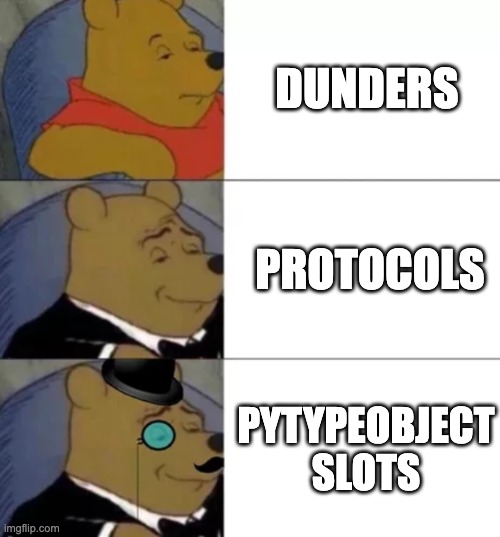

You are now Fancy the Pooh

Let’s recap the Pythonic connection with one last meme...

if you know your dunders, you’re good

if you know your protocols, you’re cool

if you know how dunders and protocols shake hands via pytypeobjects, you’re fancy the pooh

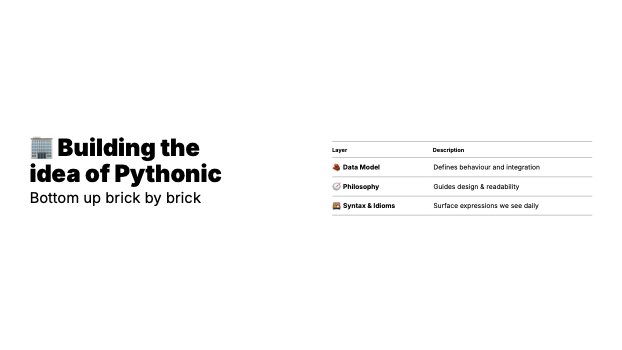

🏢 Building the idea of Pythonic

Bottom up brick by brick

| Layer | Description |

|---|---|

| 🧱 Data Model | Defines behaviour and integration |

| 🧭 Philosophy | Guides design & readability |

| 🍱 Syntax & Idioms | Surface expressions we see daily |

At its core, the data model builds the foundations of idiomatic Python. The philosophy embodies the data model and gives us those principles. Finally, there’s idioms and conventions that are the end result of that Pythonic alignment.

Most if not all Pythonic advices or tricks actually have their root in this chain.

🎬 Take 5: Being Pythonic is to align with the design and philosophy of Python

Now we have a more nuanced view on the term Pythonic..

"To be Pythonic is to use the Python constructs and data structures with clean, readable idioms."

🖋️ Martijn Faassen, author of lxml

- What is Pythonic blog post

And I have a quote from a wise man to back it up..

Martin Faassen the author of the lxml library wrote that

"To be Pythonic is to use the Python constructs and data structures with clean, readable idioms."*

🫵 How does this help you write Pythonic code?

Okay so we have talked a lot about what Pythonic is and why it is Pythonic but..

A hypothetical scenario: Gangstagram

Build an Instagram competitor

Users can add photos

Users can create photo albums and categorise photos in albums

Let’s assume we are going to build an instagram alternative. We will call it Gangstagram.

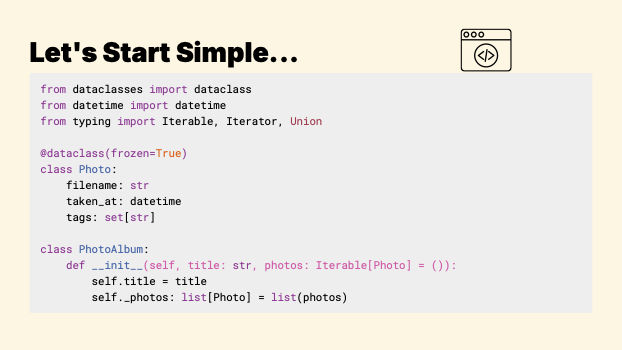

Let's Start Simple...

from dataclasses import dataclass

from datetime import datetime

from typing import Iterable, Iterator, Union

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Photo:

filename: str

taken_at: datetime

tags: set[str]

class PhotoAlbum:

def __init__(self, title: str, photos: Iterable[Photo] = ()):

self.title = title

self._photos: list[Photo] = list(photos)

We create a Photo class and a PhotoAlbum class that will hold collections of Photos. We want to write these classes in a Pythonic way.

“To build Pythonic objects, observe how real Python objects behave.”

🖋️ Ancient Chinese Proverb as narrated by Luciano Ramalho in Fluent Python 🤭

Here’s some more wisdom from Fluent Python. An ancient Chinese proverb that inspired me to bring back Socrates in this talk. Luciano writes,

“To build Pythonic objects, observe how real Python objects behave.”

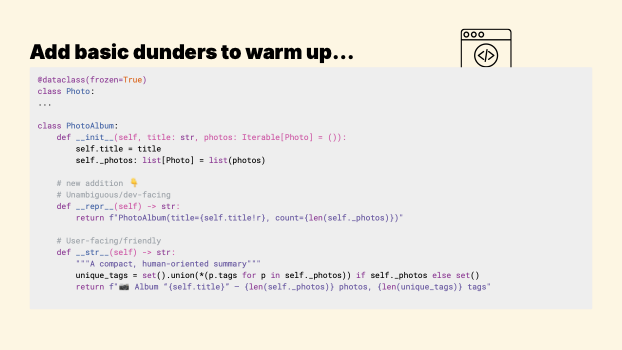

Add basic dunders to warm up...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Photo:

...

class PhotoAlbum:

def __init__(self, title: str, photos: Iterable[Photo] = ()):

self.title = title

self._photos: list[Photo] = list(photos)

# new addition 👇

# Unambiguous/dev-facing

def __repr__(self) -> str:

return f"PhotoAlbum(title={self.title!r}, count={len(self._photos)})"

# User-facing/friendly

def __str__(self) -> str:

"""A compact, human-oriented summary"""

unique_tags = set().union(*(p.tags for p in self._photos)) if self._photos else set()

return f"📷 Album “{self.title}” — {len(self._photos)} photos, {len(unique_tags)} tags"

So we have observed how real python objects behave by looking at the data model. Now our job is to mimic that. So what do we do? We add dunders!

Let's check dunders in action...

p1 = Photo("dawn.jpg", datetime(2025, 6, 1, 5, 55), {"sunrise", "nature"})

p2 = Photo("lake.png", datetime(2025, 6, 2, 7, 10), {"water", "nature"})

album = PhotoAlbum("Summer Trip", [p1, p2])

print(repr(album)) # PhotoAlbum(title='Summer Trip', count=2)

print(str(album)) # 📷 Album “Summer Trip” — 2 photos, 3 tags

And the dunders work their magic! __repr__ and __str__ now gives us different string representations of our objects and we can use them as necessary.

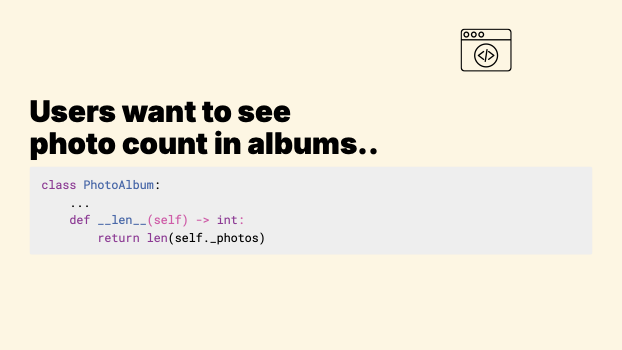

Users want to see photo count in albums..

class PhotoAlbum:

...

def __len__(self) -> int:

return len(self._photos)

Gangstagram is getting popular. Our users or, Gangsters want to see how many photos they have in each album. What do we do? We add a dunder len!

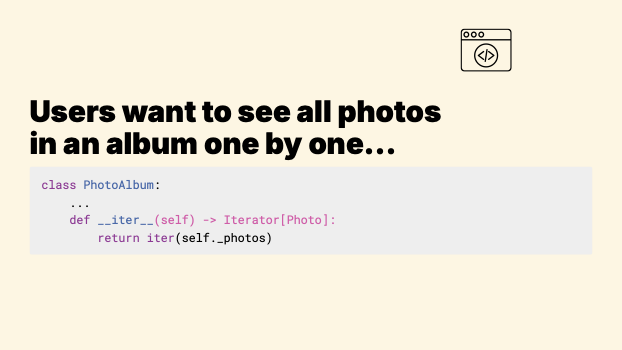

Users want to see all photos in an album one by one...

class PhotoAlbum:

...

def __iter__(self) -> Iterator[Photo]:

return iter(self._photos)

Gangsters now want to swipe through photos in albums. We bring out dunder iter to support iterations!

Effortless implementation...

print(len(album)) # 2

for photo in album: # iteration works

print(photo.filename)

And voila! Idiomatic Python shows us its beauty. Our album object has Pythonic nirvana. The code is concise yet familiar and readable.

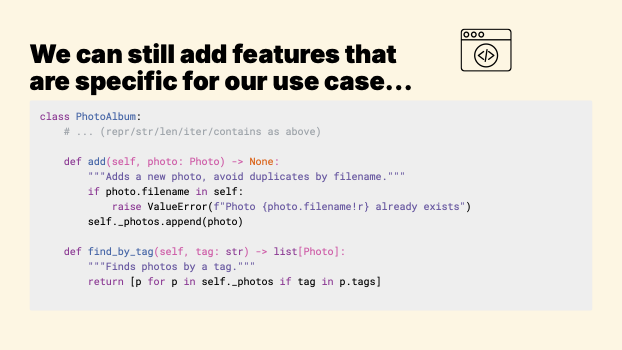

We can still add features that are specific for our use case...

class PhotoAlbum:

# ... (repr/str/len/iter/contains as above)

def add(self, photo: Photo) -> None:

"""Adds a new photo, avoid duplicates by filename."""

if photo.filename in self:

raise ValueError(f"Photo {photo.filename!r} already exists")

self._photos.append(photo)

def find_by_tag(self, tag: str) -> list[Photo]:

"""Finds photos by a tag."""

return [p for p in self._photos if tag in p.tags]

By the way, we can have our cake and eat it too! If gangstagram needs custom features, we can add those too. For example, an add feature or find by tag feature can be easily added as regular methods.

Key Takeaways

We demystified the term Pythonic! Let’s recap the main ideas.

Don’t Fight the Language

Let go of habits from other languages.

Don’t Overcompensate

You don’t need clever one-liners to be Pythonic. In fact quite the opposite.

Prioritize Readability

Future you — and teammates — will thank you. Remember the Zen, readability counts.

PEP-8 is How You Dress Your Python Code

Standards let you write code that is recognised and easily understood by other Python developers. Dress your code like a Pythonista!

When Writing Classes — Embrace Protocols

Python gives you all its superpowers, enjoy responsibly.

.png)

Use the Zen as Your Compass

The zen of Python is condensed Pythonic wisdom. Let it be your guide.

"Being Pythonic is a philosophy, not a standard"

🖋️ Daniel Roy Greenfeld

Remember, Being Pythonic is a philosophy, not a standard"

Style guides and standards may differ, but they all share the same philosophy. Just like Oogway, Shifu and Po have very different styles, yet they all love Kungfu and embody the values.

💚 We kept drilling away at the truth. Socrates would be proud!

The socratic method really came in handy today!

❤️ Thank You

Recommended Reading

- Socrates: The Badass Godfather of Uncertainty from More To That blog by Lawrence Yeo

- Fluent Python by Luciano Ramalho

- What is Pythonic by Martijn Faassen

Acklowedgements

- Rahat Samit and Janusz Gregorczyk for being my beta audience

- Lawrence Yeo, my favourite internet philosopher for the awesome article and illustrations on Socrates. Visit moretothat.com

- Luke Merett, Daniel Greenfeld for their thoughts on the topic

- GenAI & LLMs for visualising my ideas and Socrates

- Luciano Ramalho and Martijn Faassen for their authorship on the topic