Unpacking Complexity: Matching Evaluation Approaches to Different Types of Complexity

T. Delahais

Dansk Evaluerings Selskab - 11 September 2025

"You know, it's complex"

... Is complexity the perfect scapegoat?

The reason why

... policies fail

... they can't be easily evaluated

... evaluations are not being used

...

But it is also the reason why

... policies sometimes succeed against all odds!

... you need evaluation in the first place?

"You know, it's complex". You've heard that before, right? Complexity is often used as an excuse and viewed in a negative way. But it is also our raison d'être. If outcomes could be delivered through meticulous preparation, the correct choice of instruments, and the right implementation – well, you wouldn't need evaluation actually, you would just need good quality design.

Complexity is a fundamental property of the real world, characterised by multiple interactions between its multiple components, to the point where causal relationships are highly uncertain and ambiguous (adapted from Morin, 1988).

For me, it is important not to see complexity as an issue, but more as a fundamental property of the real world. I am French, so I'll use a definition of complexity provided by Edgar Morin, who has devoted the last 45 years to complexity (He's 101 years old by the way. Apparently, complexity keeps you healthy).

Morin reminds us that complex means 'threaded together'. What characterises complexity is the multiplicity of interactions, to the point where causal relationships are highly uncertain and ambiguous: you can't predict what will happen. And what is true of the world is also true of the interventions by which we try to change the world.

Once we've said that, the real question for us evaluators is what we should do about this complexity.

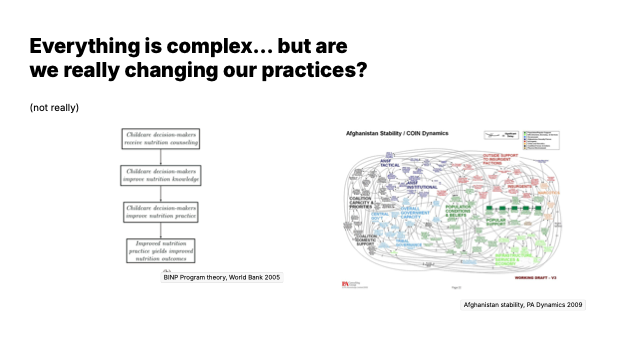

Everything is complex... but are we really changing our practices?

(not really)

If I'm trying to simplify a little bit, and I'll use a recent article by Huey T. Chen et al. on this ( 2024 ), if you want to evaluate impacts in the complex, you have two radical positions: reductionist approaches and systemic approaches.

Contrary to what some people believe, Reductionist approaches - the one we find in RCTs for example – don't reject complexity as a fundamental property of the real world. Rather, they argue that complex objects cannot be fully understood, and so it is better to break down these objects into simpler ones, verify 'what works' and then develop interventions that can be applied in any context. So their logic is not to take a complexity lens - rather, it is to develop knowledge that can be used to reduce complexity in the future and make outcomes less uncertain.

Systemic approaches on the other side obviously acknowledge complexity. But then their conclusion is the opposite: does it make any sense to evaluate a single intervention when causal relationships are so uncertain and ambiguous?

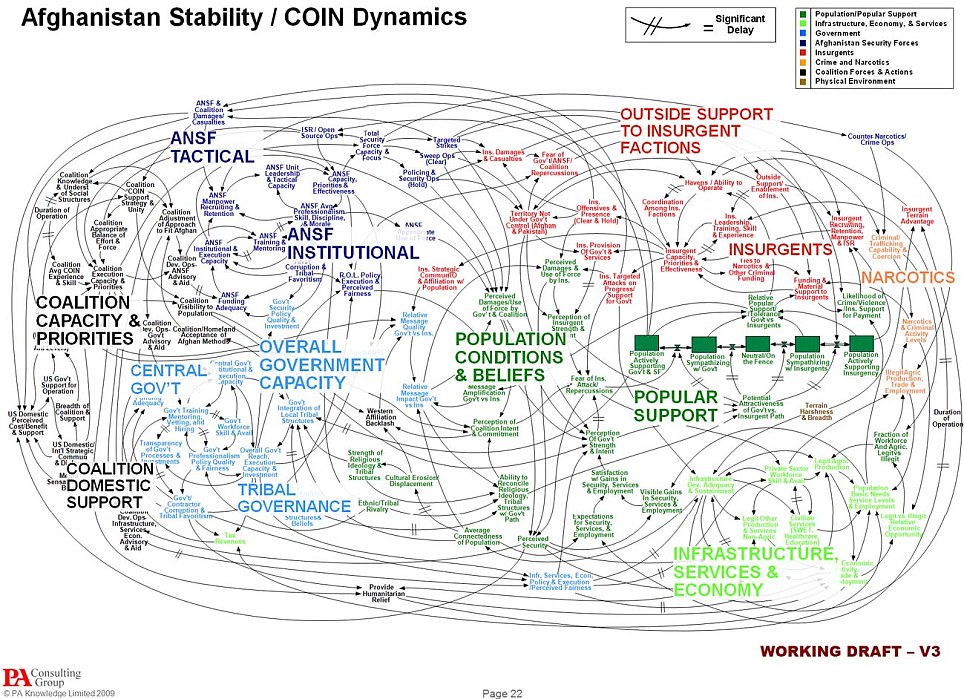

I'll make a very broad distinction here between those people who are interested in system dynamics, and those interested in system emergence (Lynn & Coffman 2024):

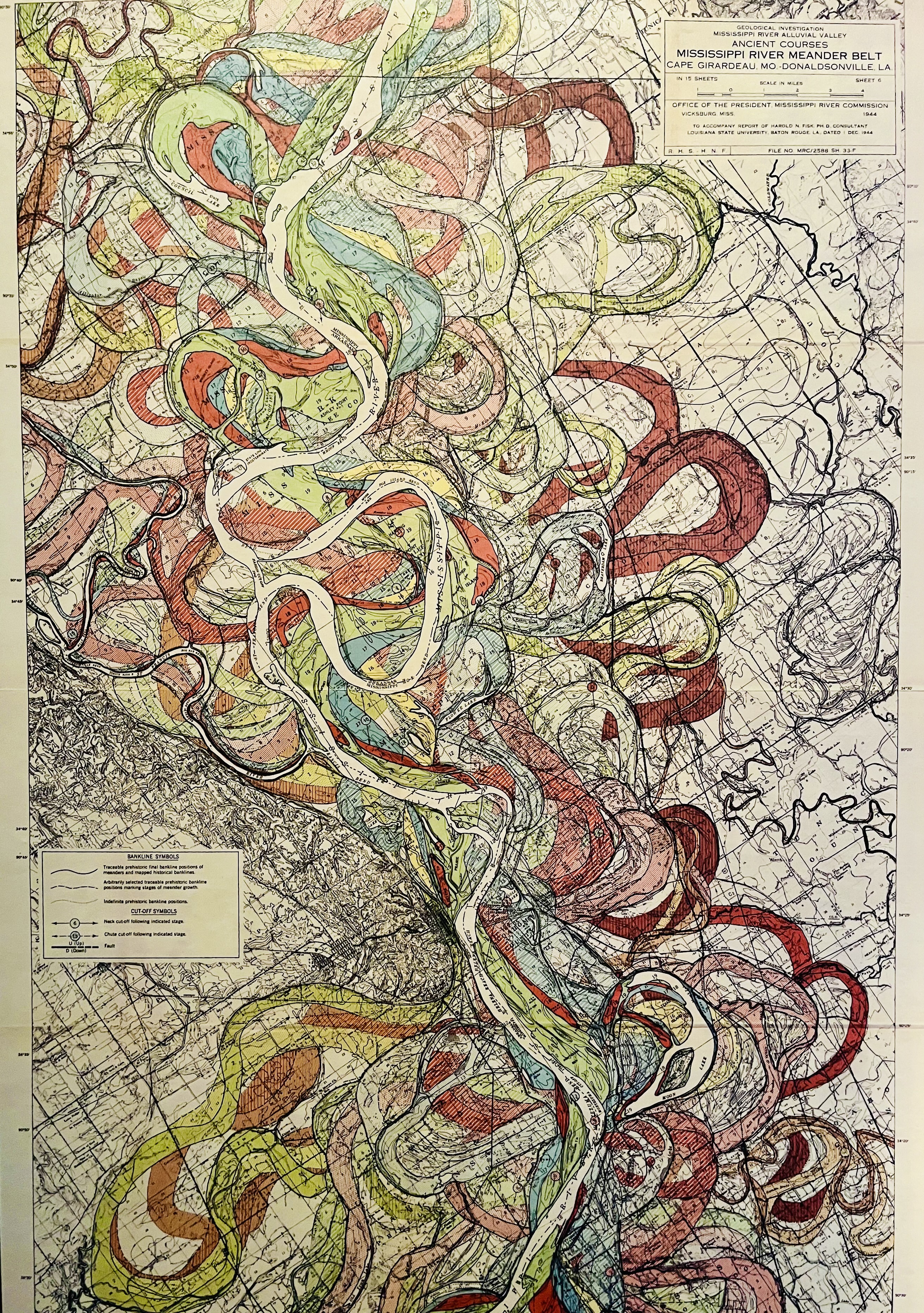

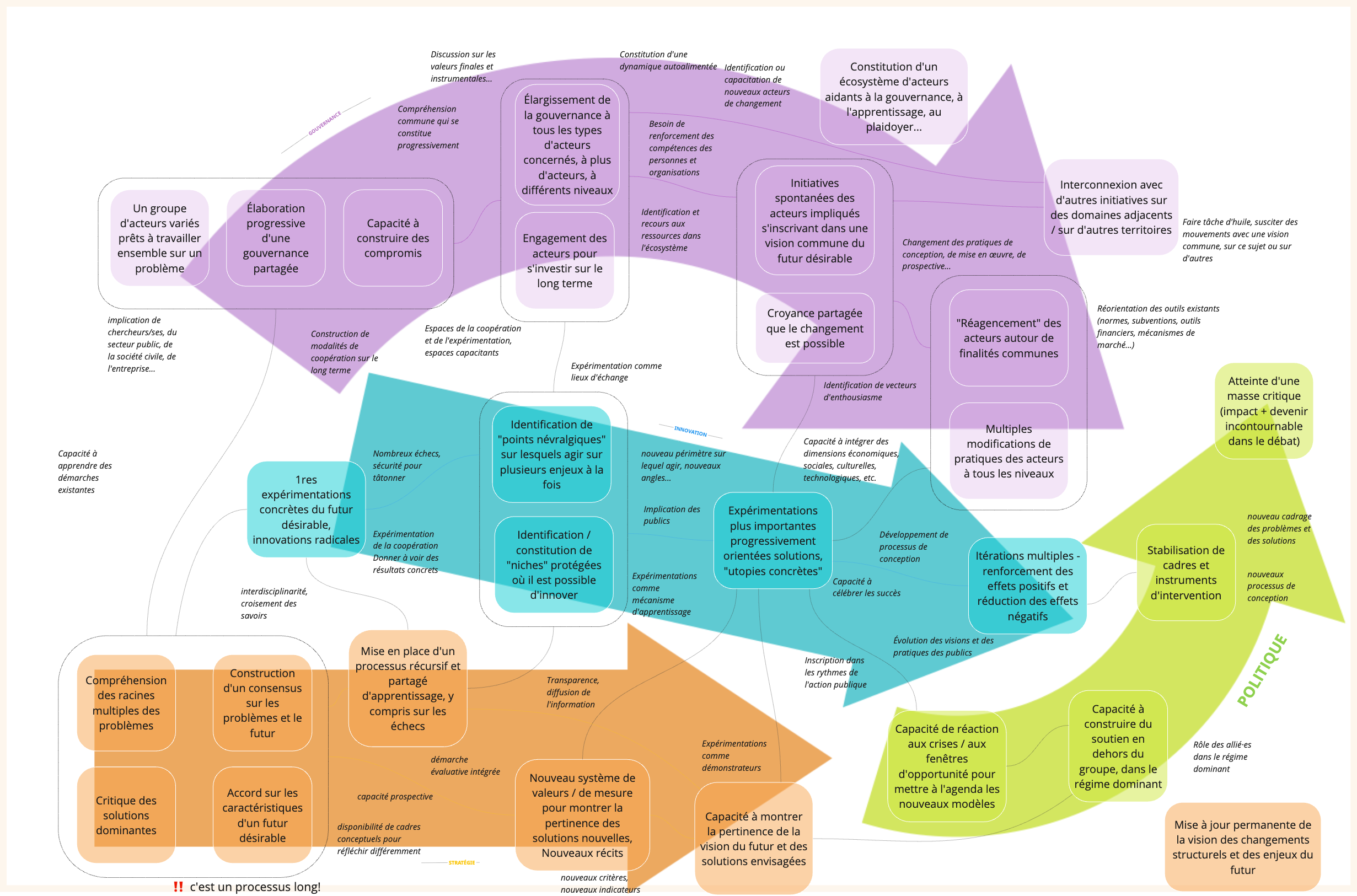

The first are primarily interested in mapping the system, identifying its components, their interactions, etc - in the hope of finding 'hotspots', or 'pressure points', where systems could be influenced. That's what you see on the screen. These sorts of maps can be particularly useful for reflecting on the relevance and coherence of interventions – but they don't tell much about whether an intervention is making any sizeable difference.

The second are more interested in carving a niche in which innovations can emerge, grow, and possibly replace the old ways of dealing with problems. But these people are not very interested in the outcomes of a specific intervention either, because they live in the future. They are more into action, constant evolutions, etc. They argue, and I think rightly, that evaluators, who are looking into the past, wouldn't see good innovation even when in front of it, because innovation is good in the future – so what's the point?

Chen call those in the middle 'pragmatic', which is true. But my view is that this is not so much about being pragmatic as being kind of caught in the middle. In reality, 'pragmatic' evaluators acknowledge complexity, but they are not changing so much their practices. There are many reasons for this:

one is that in many cases that will mean going against the grain – when Terms of reference ask you to check if the objectives have been reached or to look at specific projects without looking at the rest, it's very hard to suggest to take a complexity lens...

another is that it is also quite often simpler or acceptable to leave complexity aside, or to limit the complexity to some very specific aspects - especially when the budget is low, you have no time, no data... There is only so much that we can do.

and of course, it's also very hard to do! There is no single way or method. Taking on complexity introduces a lot of uncertainty in the evaluation process, you can get lost in too much complexity, and this leads to a risk of failure that many of us evaluators, who are working on public procurement, simply cannot afford!

Unpacking complexity is not just about choosing the right method – it is also in itself a way to evaluate and learn from the intervention

I don't want to go into too much detail about the reasons for not taking up complexity, but what I want to explore with you, which I think is underestimated, is the process of unpacking complexity.

A problem we have is that we are thinking in terms of solutions. "You have a complexity problem, use method X to solve it". There are a lot of these methods. Perhaps you have been using Contribution analysis or Realist Evaluation, or QCA, perhaps you did a participatory system mapping, or a network analysis, or you're experimenting with Big Data and AI to catch intangible impacts – Well, I did all these things. They are all very good approaches and methods, but they are also complicated, they're prone to fail, our clients want to have the fancy name on their evaluation but not the costs and the risks, and so on.

What I suggest here is that we are approaching the problem from the wrong angle – that the process of unpacking complexity, and the various types of complexity that there is to look, should come first.

And I'll argue too is that this process of unpacking complexity is not an additional thing to do, on top of the rest, but that it is actually a way to evaluate and learn from an intervention.

- There is not 'one complexity' but different types of complexities

- Complexities can be used as different lenses to look at an evaluation object from different perspectives

- Beyond the 'complexity diagnostic', it is possible and useful to engage with complexity all along the evaluation, as in an investigation process in which you make progress and identify progressively what there is to learn.

- This makes the process of evaluation more uncertain and uncomfortable, but also potentially more relevant, more engaging, and ultimately, more useful.

This being said, here are some ideas that I would like to convey in this presentation:

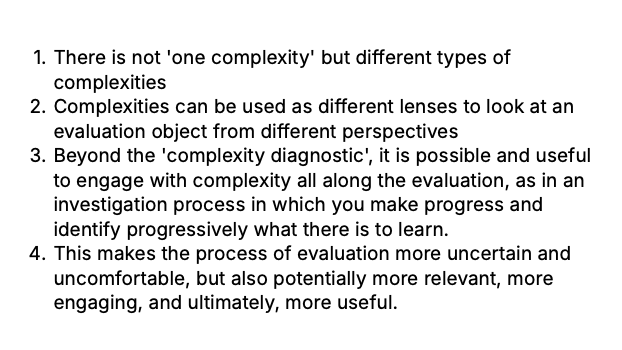

Many complexities...

I said that there are different complexities in evaluation, and when I'm saying this, I'm not just saying that there are different properties of complexity (for a roundup of properties of complexity, see Pawson 2013) - though it is true, of course.

Rather, what I'm saying is that when we're discussing complexity in evaluation, we're referring to quite different things. To show this, I want to use this diagram, which is based on a work we've done very recently about the Evaluation Journal, for its 30 years (Delahais, Thyrard, upcoming). It shows all the articles which mention complexity or systems either in their title or as a keyword – and in the middle, those papers which mention both.

As you can see, complexity is not new in the field of evaluation, but it has gained a lot in popularity over the last 30 years, and especially since the 2010s. Those articles now routinely represent between a quarter and a third of all articles published annually.

But what you can also observe is different waves in talking about complexity, which are all about evaluation but which differ significantly.

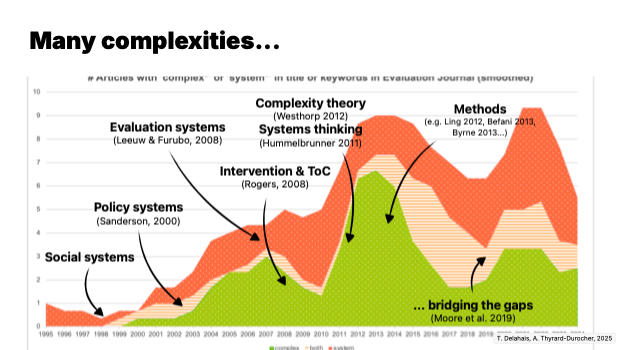

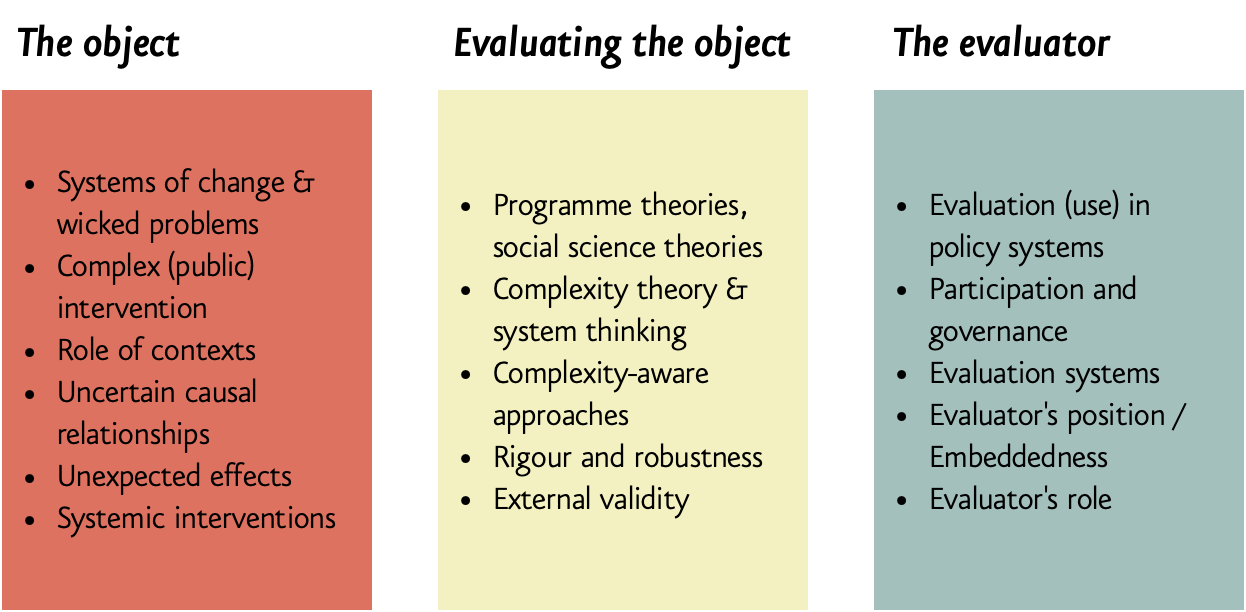

Complexities in evaluation

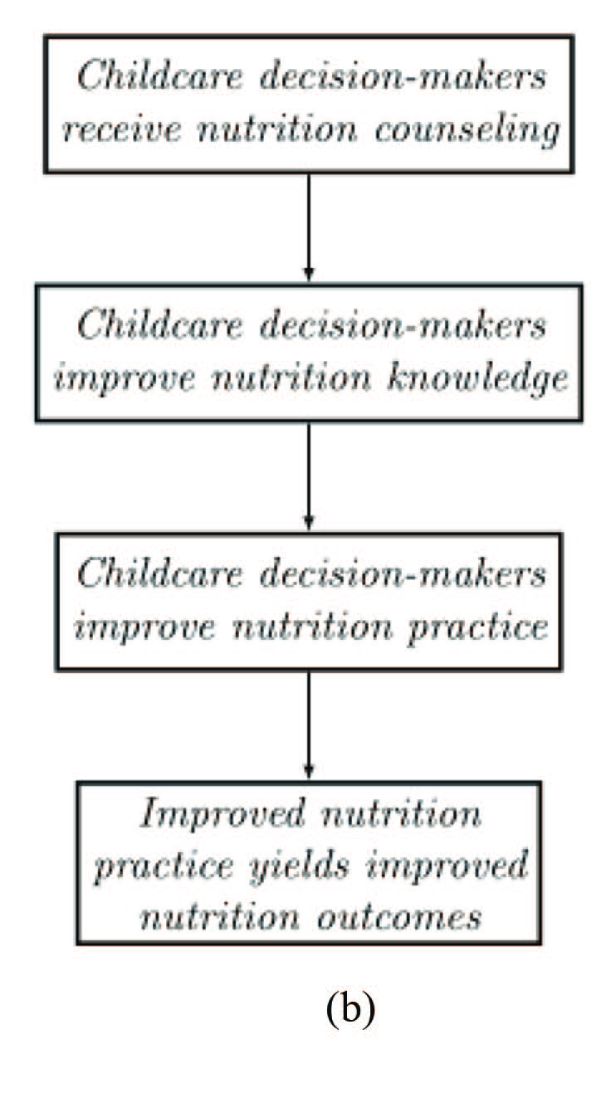

For the sake of this presentation, I listed these complexities in Evaluation articles, and I made three big groups. One is about complexity in the evaluation object, the second in how we evaluate, and the third on the position of the evaluator. Now I'll going through these three groups, starting with the first, the object.

The discussed topics include:

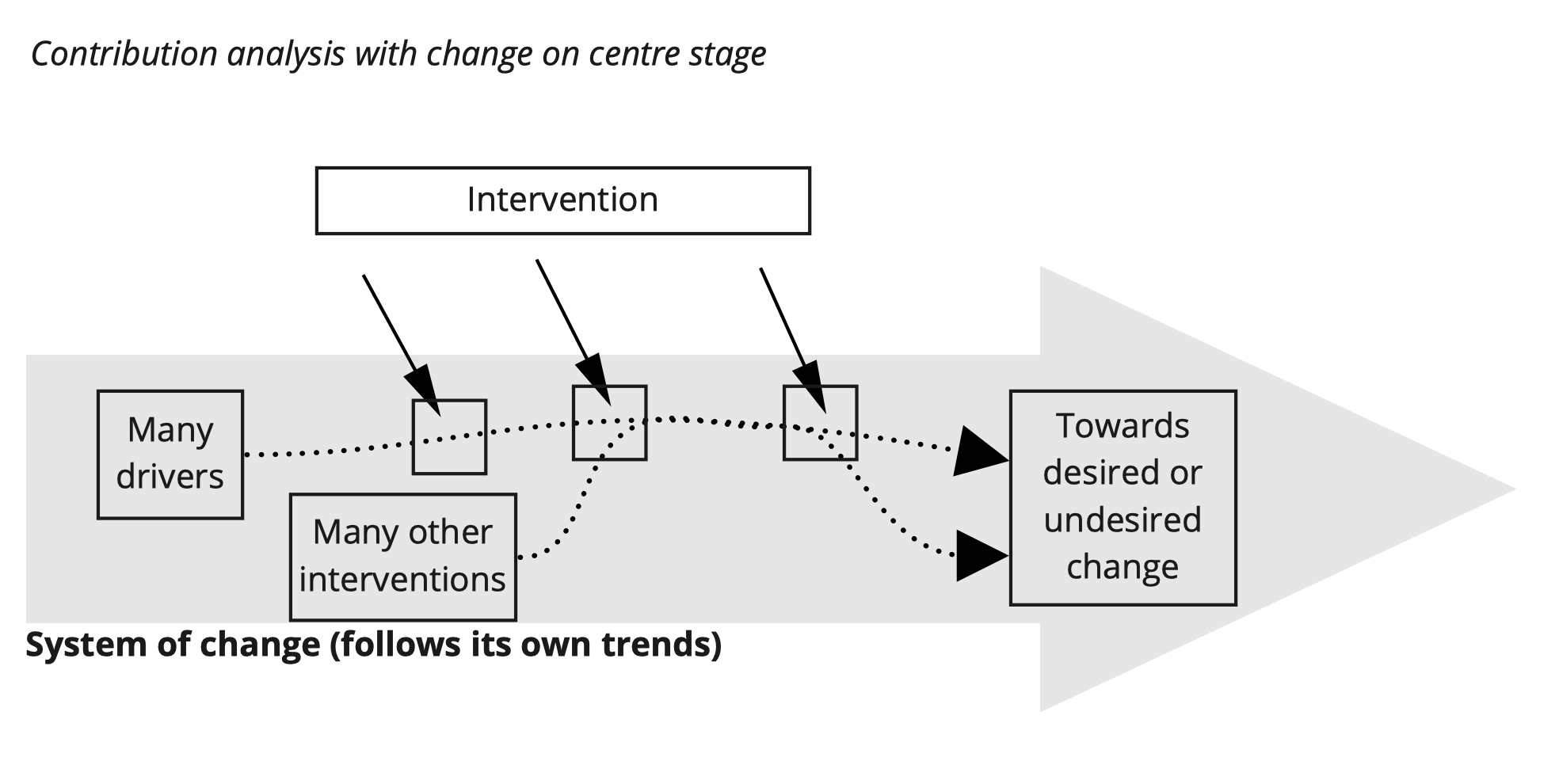

- Complex systems of change, with complex, 'wicked' problems, which cannot easily be addressed - that's perhaps the most ancient understanding here. One important aspect is considering how these systems are actually changing while the intervention is implemented, and sometimes even during the evaluation itself. Taking into account that systems are dynamic and not static is a huge challenge for us in evaluation. Another important aspect of considering systems of change is that it shifts the perspective on the intervention, which is not anymore first and foremost, but becomes one driver of change among possibly many others.

- Complex interventions, which include many components interacting with each other, or which rely on human agency and interactions set in a specific context. This is particularly visible when you change the scope of the evaluation and that you're not evaluating anymore a single programme to support entrepreneurship, but that instead you start from entrepreneurs and consider all the programmes they can rely on to get support – and then this creates a very complex landscape, with many interactions between the different actions, which affect potential beneficiaries and so on.

- Complex causal relationships, in which the results that can be obtained from the intervention(s) are uncertain, because they depend on multiple assumptions about the context, the intervention, the audience and so on. In the complex, everything may work somewhere and nothing works everywhere. So it is a bit hard to evaluate in terms of the intrinsic merits of a given policy. So an entrepreneurship policy may work in some place and not in others, and sometimes it's not because it is good or not, but because of how it is used by some local operators, how it fits their agenda or not... What makes things work is more arrangements of interventions, actors, places and technologies, and effects are best understood in terms of one or several causal pathways than in terms of a linear relationship.

- Unexpected effects, which is not something new in evaluation, but which takes a more important role once you're not thinking so much in terms of reaching objectives, but rather in terms of changing systems. And you don't always know what changes systems. Typically, an entrepreneurship policy might be more valuable because it fosters a culture of trial-and-error, for instance, than because it created jobs.

Connected to all of this comes the realisation that the judgement we make about an evaluation object might change a fair bit depending on the scope – in terms of interventions, but also in terms of timescale, places, publics, considered effects and so on (e.g. Woolcock 2013 ). And so the sensitivity of the evaluation to the scope makes it almost impossible to make a definitive judgement about something. This is not new, but becomes extremely clear when considering complexities.

A final thing in this category is that in the last two decades, we have seen the emergence of interventions which have been designed, or are implemented in a way which acknowledges complexity. Think of systemic design, of adaptive governance and so on. And for these interventions you come to a whole new question, which is: Can you evaluate a systemic policy with a conventional approach? In my experience, you can – but doing so is the best way to kill it. So evaluators should be careful about this.

A second group of complexities that we can see in the Evaluation Journal and in the literature in general is about the ways in which evaluation can deal with this complexity. Here I will cite:

- the use of theories, which is crucial - we are talking about programme theories, with the critical distinction between a theory of change and theories of intervention. The theory of change is how you make sense of the broader system, and I think that it is a crucial thing to do in an evaluation – trying to think not only about the intervention, but also about the system of change – I'll give an example later

- ... Another topic is the use of social science theories to make sense of processes of change, of the intervention, of the behaviour of actors, and so on. Because we are talking of complex objects, very often the challenge is that we have to combine different theories.

- And a final sense of using theories here is how you use complexity theory and system thinking in support of your evaluation, for instance as a way to understand the processes of change at stake - you can think about questions such as the instability of systems, the emergence of new problems and solutions, dealing with crisis and so on.

- Then there are the different approaches and tools which are being developed with a view to take complexity in consideration. What was particularly important on the evaluation scene in the last 25 years was how different ways of thinking about causation and causality have offered us new ways of thinking causal relationships, and moving away from the counterfactual logic to think in terms of configurational effects or generative effects ( Delahais 2021 ).

- Associated to this is the debate about what constitutes rigour or robustness in complex settings, when the object that is being evaluated cannot be fully known, because it is intangible, or because there are too many situations to investigate and you're only seeing a part of it and so on ( Apgar et al. 2024 ). And with this comes the debate on the level of uncertainty which is acceptable about success or failure.

- One last important discussion has been on external validity, or perhaps more how you generalise, transfer or replicate when you know that success or failure depends on the actors, the place, the interactions and so on ( Yin 2013, Delahais 2025). On this too I'll give an example later on.

The final group of complexities that I want to present here is about the complex contexts in which evaluation unfolds and which may explain why an evaluation is being used or not, and the questions it raises about the role of the evaluator.

Probably one of the biggest and longest debates in evaluation is about evaluation use. It's been more than 25 years that everybody agrees that you can carry on the best evaluation in the world, with the best methods and everything, and it is still not enough to make it used. And so the discussion is between those who believe that the evaluator is responsible for making the evaluation useful – by finding users and orienting the evaluation process towards making the evaluation useful to them – and those who see evaluation primarily as a process within broader policy systems, and who therefore say that use happens at the level of this system, not at the level of the single evaluation. Think Patton on one side, and people like Weiss, Chelimsky or Stame on the other side. And so of course that second approach means thinking in terms of evaluation systems, in which you think more in terms of information flows and their roles in organisation, in governance, in decision-making, in adaptation and so on.

Another subject of reflection, which is not new either (Coulson 1988 ), is about the position of evaluators in the processes that they are expected to assess. This is a discussion which was very strong already in the 1990s in terms of evaluating innovation ( Finne et al 1995 ), and which I think is particularly crucial today when we're evaluating public or social innovation. And these innovative policies, especially when they're adaptive, or agile, are often very unstable, so it is not possible to define the evaluation object at the beginning, or what success looks like, and even less a data collection plan. So they call for an evaluation which is embedded in action, but this also introduces complexity because it changes the relationship, it involves mechanisms which are not just about an empirical feedback, but also about caring, supporting, sharing common goals and so on.

And all of this, in general, triggers many reflections about the role of the evaluators, how their practice reflect the systems of which they are part of, and so on.

... So that's a lot of different understandings - perhaps you can think about which of these understandings you include in your practice today. Perhaps you're ticking all the boxes. But I don't think you are ticking all the boxes on each of your evaluations. I mean, there might be a few super-heroes among us today, but in general, you will not be able to address all these complexities. And you should probably not try!

What I'll suggest here is rather a few ways to look at these complexities. I will not talk so much about the methods themselves, that's a subject of its own, but I will try to give some examples of pragmatic strategies in which you can engage with these different complexities, and see what we can learn from that.

Four examples of unpacking complexity along the evaluation process

How did research contribute to sustainable forest management in the Congo Basin?

How far does the Cohesion policy influence innovation policies across European countries and regions?

What are the social, economic and environmental impacts of the Paris-Bordeaux High-Speed Railway?

To what extent can we learn from bottom-up Transition initiatives and replicate their success?

To do so, I'd like now to talk you through four examples of this sort of absurdly complex evaluations that we are expected to carry out. For each of them, I'll explain what the evaluation was about and the complexity challenges we faced; but what I really want to show you is how the unpacking of complexity was a common thread of these evaluations, and how it contributed to make them useful – not always as expected, but still.

Starting from system of change (CIFOR)

My first example is a case in which most of the complexity was in understanding the system of change and trying to understand the role of the intervention in that system of change. In 2012, we were contacted by the CIFOR to evaluate the contribution of research to sustainable forest management since the creation of the CIFOR 20 years before (Delahais & Toulemonde 2017).

It's a very clear example in which complexity stems from the ambition of the scope. They were not asking about the effects of their research projects, for instance; nor were they looking for a sort of coherence assessment - as in whether their objectives were aligned with sustainability goals. They had a very clear problem: Their main funder was accusing them of being useless and was threatening to stop their funding. And so, they had to prove that they had an influence on something that actually mattered to policy makers, and that was deforestation, which is not the sort of reasonable intermediate outcomes that evaluators usually look at!

And they were in a situation which was a bit paradoxical, in which it was very clear that research could have contributed to sustainable forest management, and in many different ways, but it was also very clear that it was not the sole contributor, and probably not the main one.

Our chance in that case is that we were working with researchers and that there was a lot of existing knowledge about sustainable forest management, and this allowed us to do two things.

The first was to draft a system of change, in which we used existing knowledge to come to a sort of model of how forest management in the area had become more sustainable, and this model was organised along the main actors involved.

And the second was to collect claims about how those actors could have been involved, could have used, or been influenced, by CIFOR. We collected these claims with CIFOR people, with policy makers, with multilateral organisations and so on, and we ended up with 50 claims or so, which we progressively aggregated into 5 main claims. And these claims were that CIFOR had contributed to frame forestry issues in a certain way; that it provided data which was useful to policy makers and to businesses; that it helped in the implementation of legislation favourable to sustainable management through pilot projects and experiments; that it helped in raising the capacity of stakeholders in designing and implementing forestry-related policies; and that it helped in the operationalisation of the policies, for instance through management plans.

And this is what you see in the diagram in the screen, and what you can see is that we didn't really look at their actions, but rather, we started from the system of change and we asked: where was your contribution? And this was an iterative process of agreeing on the system of change, on the directionality of change, and on the contribution claims.

The way in which this sort of logic is useful, is that once we had something stable enough, we used it to sort of 'carve a perimeter' in the system, in which a contribution was plausible. So we did not follow a holistic logic, trying to understand everything in the system. What we said was more something like: "there are other reasons which may explain how the forest is managed, like war or international trade, but any contribution of the CIFOR to these are unlikely, so we'll acknowledge them, but we will not spend more time on these".

And after some time, we tested these claims with national and sectoral case studies. In doing so, we followed two principles. One that it was unlikely that CIFOR would have an impact alone – and so we tried to identify causal packages, which were a set of interventions, conditions etc. which were explaining influence. We also tried to identify and assess rival explanations when they were better at explaining. And the second was to assess their contribution claims not so much in terms of 'is it working or not', but in terms of necessary or sufficient conditions for change. And in the end, on the 50-or-so claims we had at the beginning, we identified 7 cases in which CIFOR's contribution was necessary or sufficient, and that means that on that basis, CIFOR could face its funders and show that it had an important role in slowing down deforestation.

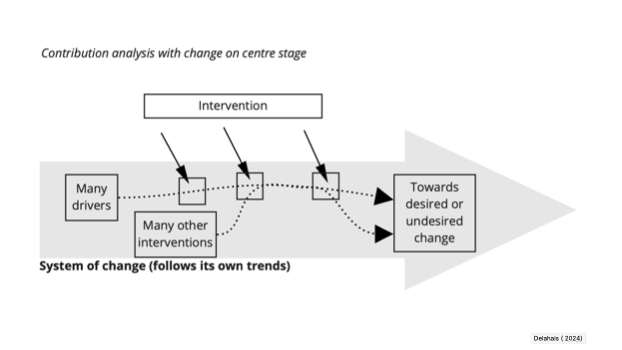

This is the sort of logic which you can see in the diagram on the screen, where the process of unpacking complexity means 1) taking a broader perspective about change; 2) acknowledging that you will not be able to estimate the value of an intervention without taking into account what else is happening at the same time. And the important tools we had to do this were two things:

- theories - the programme theory, and social science theories

- and causal thinking which was new to us at the time, "configurational thinking", in terms of sufficient or necessary conditions, which really helped us think this through.

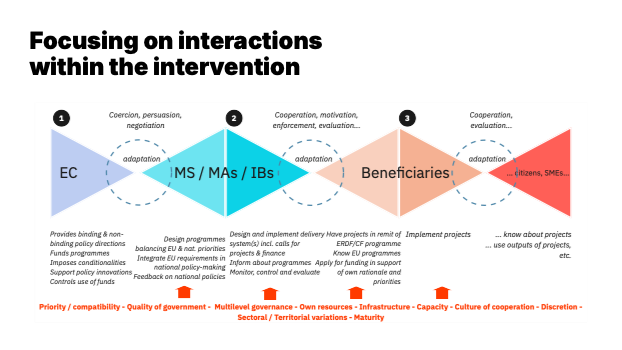

Focusing on interactions within the intervention

This second example is based on the evaluation of the European Regional Development Fund, which is one of the European Union's main instruments to support development and convergence across the EU. And in that case the complexity is mind-boggling, because you're talking about 300 bn. euros, through dozens of different instruments, implemented by hundreds of managing authorities, thousands of implementing bodies, millions of beneficiaries... and different contexts for each of them. And I should add to this that the ERDF is a spending programme, but over the years it has become much more than that, because it also supports some specific policy orientations, some specific concepts and so on.

So there is a lot of complexity here, it is not your usual evaluation, but here I will focus on one aspect of the evaluation, which was really the implementation. One of the challenges is that the European mindset is very topdown, so they think in terms of delivery. They turn on the tap and they wonder how much money gets on the field. And what they often fail to consider is that all these actors who are involved in the very long chain between the EC and the field, they all make their own choices, which depend on their own policy context, on their own resources, on their own capacities, and so on.

And the thing is that, in all countries, in the end the money gets on the field. So if you're just measuring what happens, you'll say, "there is some delay but it works". We've seen that in many evaluations of EU funds. But the thing is that it's a lot of money, so all the actors above they might do many things to get it, and this may not be what was wanted at first.

So what we did in that case was to focus not so much on the result but on the interactions: what is happening in the relationship between the European Commission and Member States; in the relationship between Member states and beneficiaries; and so on. And of course, that is interesting, because you have some sort of adaptation process which is going on, not only at the beginning, when there is a new programme and a process of contracting the money, but also all along the implementation. And this process of adaptation is interesting because it largely explains why some regional programmes are much more effective than others; and it also explains why some programmes are very effective in local or national terms, but not in European ones. And it is also interesting because you can identify conditions to implement to make this process easier, and which are not just "simplification".

So if I'm taking a very specific example, ten years ago, the EU has started supporting a new type of innovation policy, what they call 'smart specialisation strategies' or S3s, which we very new in that, instead of saying, "let's build the research infrastructure first, and then research will come", they say, "let's find innovative entrepreneurs first and then let's make it easy for them to expand, to make the right connections and so on". I'm simplifying. And of course, this is completely different if you come with an idea like this in Denmark, which has a lot of thinking going on on this question, which has a huge ecosystem of innovation, and when you do this in Bulgaria, which doesn't have the ecosystem, and which is hugely dependent on the EU for funding research and development. But of course, formally, everybody has adopted the S3, so for the EU it is not really an evaluation question. However, the consequences are huge, because if the S3 is formally adopted but the policy is the same as before, and it is very far from the S3 mindset, then you can't possibly have the expected impacts.

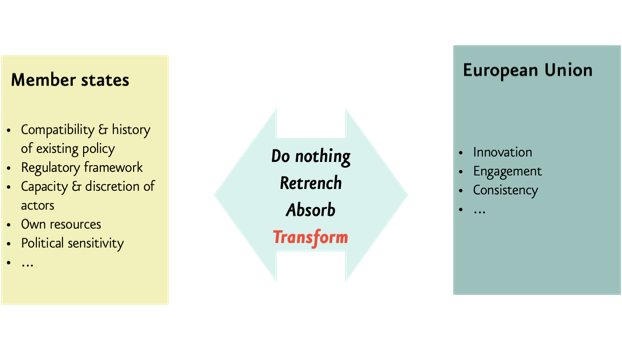

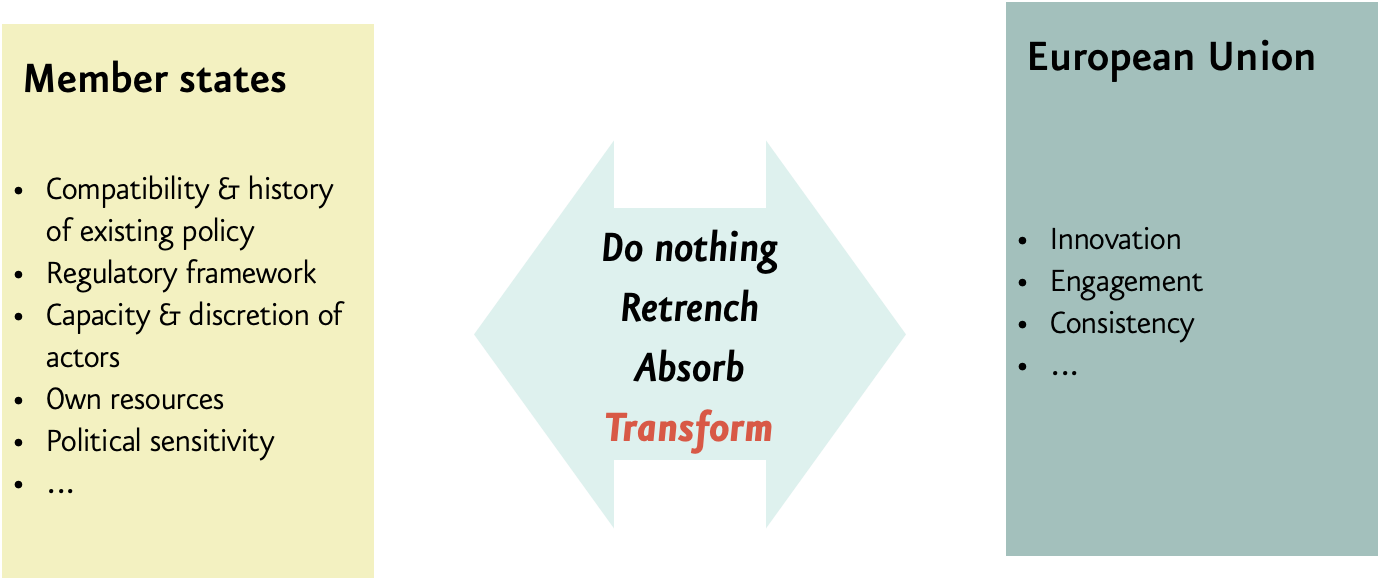

So what we did in that case was to rely on academic literature, and especially use what is called the 'Europeanisation framework'. This is a framework that look at how countries react to European policies. And it looks not only at whether policies are adopted formally or not, but also at whether countries already have a compatible policy or not, and whether it can be adapted to cope with the EU requirements, or does it need to be transformed. And in that case, do you see a real transformation, or just the same old thing but under a new name?

The question of "transformation" is important. With a conventional programme theory, you would say, well the desired goal is that they transform, so that's what I show in my theory. But what has been found in that case is typically there is very little transformation. What we have is western countries or regions which had sophisticated innovation policies, and they were mostly OK with the new innovation policy, but mostly what they did was adopt the language of the Commission and keep business-as-usual. And in terms of the evaluation, the spending is put where it should, but the transformation value is very limited. And on the other end of the spectrum, we have countries or regions which just didn't have the capacity, the skills, the ecosystem to possibly implement a sophisticated strategy like this, but they were willing to, and some of them have spent the last 10 years trying to implement something like this. And in terms of the evaluation, that means that the spending is not where it should be, but there is som potential in terms of transforming things. So that gives a much more nuanced view of the impact.

So this is a case where unpacking complexity means trying to understand the long chain of actors which connects an intervention to its expected outcomes and impacts, focusing on the interactions between these actors rather than just on their behaviours. And here you have another view of causality, which is generative, and which help think this through. And it's also a typical case where social science provides frameworks that are useful, because there is a long history of such policies - but funnily enough, this sort of framework is very rarely found in the evaluation of European policies. And it's also a case where also, I think, part of the role of the evaluation is to translate research into something that makes sense for policy makers – though I'm not fully sure it actually worked, to be honest. We'll see.

Considering a broader range of effects

The third example is a case of a large infrastructure, the HSR between Paris and Bordeaux. And this is typically a case where the evaluation, the one that really matters, has been done before - because you don't engage a dozen billion euros in a project if it's not worth it. So you have a cost-benefit analysis, which looks at the estimated socio-economic return on investment, and it has to be positive, otherwise there is no investment. And usually, the ex post evaluation of this sort of investments is very limited. It's just about the traffic or that kind of things. But it's really a paradox because you can't justify a high-speed railway just on traffic. It is sold to public investors on promises of economic development, attractiveness, tourism, quality of life, climate change mitigation and so on. You're making a lot of promises and then you just take them as granted, that how it works.

So it came as a surprise that the Regional Council of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, which is where Bordeaux is, decided to do an evaluation which would look at all the potential impacts of the new railway – economic, social and environmental, 5 years after completion. 5 years is still very early, after this kind of infrastructure, but you can still see whether some of the promises are being confirmed or not.

And we had three kinds of complexities here to deal with. One was about measuring change; the second about the potential effects of the HSR; and the third was that there were some people who were enthusiastic about the new railway, and some people who were very hostile. We had people saying that the HSR was the most environment-friendly HSR ever and others saying it had destroyed the environment. We had people saying that it was making Bordeaux more attractive and some saying that it led to an invasion of Parisians and that this was intolerable. We had people saying that it was good for tourism and some saying that this tourism was making the city suffocating, and so on.

So it's not just possible to say: these are the objectives, let's say if they were reached. Our approach in that case was rather to start from the claims about what the railway was doing. And to do this, we used the press. That's probably the evaluation in which we used the press the most, because it was all over the new railway. The newspapers were always saying 'this company came to Bordeaux because of the HSR', or 'housing prices are climbing and this is due to hoards of Parisians coming with the HSR', and so on. And when you do this, you end up with a lot of claims, which we took seriously to avoid having some stakeholders saying that we were not considering their claims seriously.

And based on this, we did two things. We had the changes measured, as much as possible. So for instance if we're saying that the prices are rising due to the HSR, what can we say about actual prices over the last 15 years? We refined the claims, into assumptions that could be tested, like: are the prices climbing because of investors or because of new home-owners? And we tested them. So for instance, we've found that most of the effect of the HSR on prices was anticipatory and was due to investors, many of them regional investors. We found that the effects on local development was very limited because local authorities did not manage to really integrate the HSR in their vision for the future of the territory. We found that the effect on climate mitigation was much stronger than expected, because the flight connections between Paris and Bordeaux became unprofitable and then were prohibited by legislation, and so on. And so, in general, the effect of the HSR was not so much what it was supposed to be in the ex ante evaluation, it was nuanced, but it was also soothing for the stakeholders involved, something they could work on.

This evaluation was supposed to help the Region improve its development and mobility policies, and I must say that it was a big failure, because at the time the Region was negotiating for a new HSR, between Bordeaux and Toulouse, and our evaluation was actually too 'nuanced' for them. So we were attacked on the robustness of our work, but once the contract for the new HSR was signed with the State, it was published at such. Where it was a success however is that all the other stakeholders, the State, the operator of the line, the local authorities, the NGOs, etc. appreciated the report and used it for future reflection or negotiation. And actually, the Occitanie region, of which Toulouse is part of, used the report to reflect on how the region could support the arrival of the new Bordeaux-Toulouse railway in 2032.

So this is typically a case were unpacking complexity meant trying to understand what an HSR does to a place and to people and businesses, but also where valuing was extremely important, with people being either hostile or enthusiastic. And I really believe that a positivist exercise of 'objectively measuring' KPIs would not have worked. Here what really mattered was to do justice to different claims, give nuanced explanations, and also give some avenues for the future, not so much in terms of 'you should do this and that', and rather in terms of 'this is what you should care about' or 'this effect is not automatic, it depends on local strategy, on community engagement', and so on.

Improving or replicating

The last example is about Bottom-Up Sustainable Transition initiatives. I've worked a lot with this kind of initiatives, which are led by local authorities or by groups of civil society organisations, or even by groups of citizens. One way of describing these people is that they try to make a desirable future happen, but not knowing what this future looks like or how to get there. For instance, one of these initiatives started 20 years ago with a willingness to provide organic meals at the local canteen, and in the process started reconfiguring the whole local food system, working with the families, the farmers, the businesses, the neighbouring local authorities, etc. And now they are building alliances with other local initiatives to upgrade, but also to lobby the Parliament and so on.

So when you're working with this kind of people, the first thing is that they are very suspicious of evaluation, which they think is part of the problem more than the solution. That's because typically, the conventional evaluations, the indicators that are used by the ministry, it all goes against them, because they're not doing the things in the way that is expected.

But on the other hand, these people have reflected a lot, they've done a lot of experimenting, and they can tell that what they've done has worked or not because they can see it firsthand, and what they've done, there is not so many other examples of. But they face some problems. The first one is of course that they are heavily criticised by people from the dominant system; and the other is that what has worked for them is very often not working with others. And one of the reason for this is that it's very hard to talk about success or failure, because they believe that everything is better than the status quo, and yet they do not know if what they are doing is really changing things in the right direction. And that is where evaluation can also be useful to them.

And here we have a paradox, which is that we are typically in the kind of situation where causal relationships which led to success in their case cannot be isolated from their context, and you can't have easy solutions to implement – but the demand for lessons is even stronger than in conventional evaluations. So as an evaluator you need to change a bit your logic.

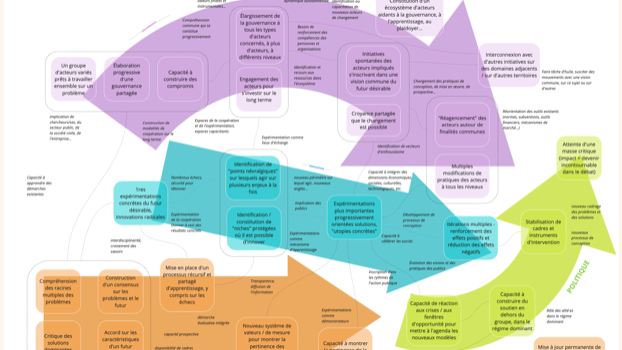

In a case like this, what we did was really three things.

The first was to investigate what was really to be generalised. When you talk with the people in these initiatives, they tend to come with 'recipes of success'. So you need to have the whole package, do exactly what they did. But these recipes won't work elsewhere usually. And that's because these recipes include many elements, and possible causal relationships, but which are very unclear, even for them. So a large part of the evaluation process in that work is to untangle the causal pathways and underlying mechanisms, try to understand what did what, to come with some generalisability claims at the end. And what we end up with is less recipes than ingredients. So perhaps not: 'do like us' but 'what really mattered was that we contracted with local farmers on the long term and that has given them time to change their practices' or 'involving kids in harvesting vegetables created an emotional link and a sense of duty among farmers'. That kind of things.

Which leads us to the second thing, which is to provide instructions for use. As we said before, from a complexity perspective, everything might work somewhere, and nothing works everywhere. The potential users of the evaluation results need to know the context of implementation and verify if it matches the context of application. This means providing thick description of claims that can answer the users' questions. So you explain how kids were involved, the time it took, the errors they made and so on.

And the last thing is, if you're providing a list of ingredients and instructions for use, you also have to help users become good cooks. Which means that the role of the evaluation doesn't end with providing the results. That means that there is a process of bringing the results of the evaluation to others, go to different cities for instance, so that potential users can not only learn, but perhaps 'simulate' the action, see how they could mix the ingredients in their own soup and see how that work. And in this case, not only did these users do the work of adapting the findings to their own case, but they also improved the generalisability of the initial results by reflecting on how those findings applied to their own experiences.

So this is typically an example of how the role of evaluation is being changed by complexity. And that means going beyond the usual scope of the evaluation, but it also changes our role and the things we do more broadly in policy making.

One example of how this is changing us, is how we may need, to some extent, to work on the longer term. In my career as an evaluator, I've always tended not to work too long with the same administration, because it distorts the relationship. But if you want the evaluation to be useful in transition initiatives, you have to support processes in the very long term - and part of this relationship is not commercial anymore. We are supporting this because we care (Delahais et al 2020). But it also creates new problems because we are not a charity and we don't have an economic model for that.

The second example of how this is changing us is how, to some extent, we may end up becoming 'theory builders' ( Guenther et al 2024 ). Because when you're dealing with complex topics, what happens is that we end up working with topics that have not been explored well before. What you're seeing on the screen is part of a work we're doing now, in which we have tried to identify some of the underlying process to transition initiatives and how they can become more mature – in terms of governance, of innovation, of learning, or institutionalisation. And the reason why we are doing this is that people involved in transition initiatives need guidance, and to some extent evaluation is one of the main sources, or at least it is the only one which is empirically funded.

Your turn: A few starting points

- Start with change, not objectives

- Investigate the interactions

- Adopt an abductive, iterative approach

- Document what is known and not know (by whom!)

- Use theories and build theories

- Use different causal models

- Engage users

- Embrace controversies

- ...

- Be humble

I'm done with the examples. I'm listing here some of the ways in which we've tried to unpack complexity. All of this, of course, means that evaluation needs to be part of a much more fluid process, one in which you progressively clarify what you want to work on. You need to leave some room for being surprised and for changing course along the way. And to do this, you need a lot of trust among stakeholders, and actually building that trust takes some time! And some of the failures I've hinted at, they were also due to a lack of trust. So keep that in mind.

I would insist that this is not easy and that in general you need to be humble, because you're never going to remove the complexity, you just shed light on some aspects. Edgar Morin, who I've cited before, used to say: "We need to learn how to navigate in oceans of uncertainty through archipelagos of certainty". I thought this was an adequate citation in this maritime setting.

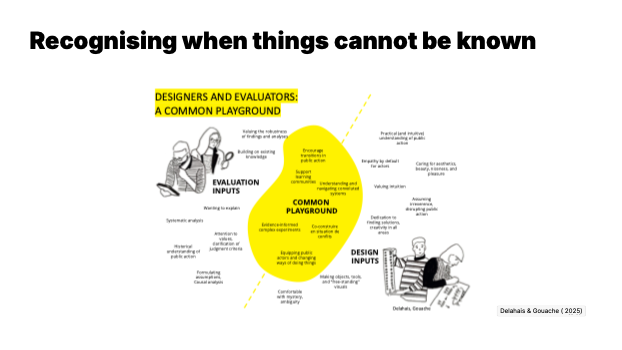

Recognising when things cannot be known

One last point before we conclude: being aware of complexity should also help us recognise when things cannot actually be known, and where an evaluation might create the dangerous illusion of false certainty.

We are probably too often like the proverbial guy with a hammer, who sees nails everywhere. Well, when you really don't know, and can't know, probably the good thing to do is to act! And one of the things we have tried to do a lot in the last years, is to work with designers – people who are much more comfortable than us with uncertainty and ambiguity, who manage to work with the whole without breaking it into parts – to test and experiment, and use our evaluative skills in support of these experiments.

This is what we've done for instance in contexts of radical disagreement between stakeholders - we've worked on designing processes to reduce water use, on ways to reinvent the Parisian nightlife, on unjamming the jammed emergency housing system in Northern France, among other very complex topics – and in all these cases, our added value was much more in evaluative thinking than in evaluating retrospectively.

Conclusion: Are we mission creeps? Or is it about keeping our profession relevant?

The late Canadian evaluator, Chris Coryn, was anxious that evaluation was becoming mission-creep and tried to do too many things. Considering the boundaries of evaluation, he would ask what was "in the tent" or "adjacent to the tent".

If I want to push the metaphor a little bit, what I could say is: well, someone took our old tent and we'd better build a new one. In my country and in others, the most sophisticated authorities, which develop systemic, complexity-aware programmes, have also developed excellent information systems. They can count on excellent, reflexive professionals who use these systems to steer and improve their programmes. They might not need us so much anymore.

You may say – 'Sure, but what about having an independent perspective? What about accountability? Isn't that important for these guys?' Well, in my country and others, many organisations are also eager to develop AI-based automated monitoring systems. There is a whole industry which is ready for that. And what they are clearly aiming for is replacing evaluation with a machine-led accountability. And perhaps there will be cases where the sort of human-led independent evaluations will be organised, but I also think that there will probably be much less of these audit-like evaluations which are the bread-and-butter of many evaluators and which sometimes remain at the surface of things.

In both cases, for these organisations to be interested in evaluation, it is my opinion that we need to give them something different, which opens up their horizons – something their systems cannot give them.

I have said at the beginning that many are seeing complexity as a problem. There are people who are working hard to remove complexity in public action, because they believe it is a liability. One way to do so is to remove agency and interactions in the system: in social and education policies, you're seeing the rise of automated decision systems, digitalisation, AI chatbots and so on. You may think that there will still be uncertainty in the context of change, in the effects on the long term and so on, and I agree! But to some extent, will anyone care? And who needs an evaluator if outcomes can apparently be delivered?

This gets me to my second and last point here: we need to defend complexity as a positive thing - and get people to navigate it rather than try to destroy it. It's not just about preserving our turf. It's because complexity doesn't just create uncertainty; it also offers chances for resilience, for fighting authoritarian or productivist regimes for instance. That means that our political engagement doesn't have to be in a political party, but rather for what constitutes political life: agency, interactions, democracy and so on.

Thank you very much.