AI in Higher Education Webinar Series

1: Teaching & Learning

18 March 2025

Here are the slides from James Ransom’s presentation at the event on AI in teaching & learning, organised by the National Centre for Entrepreneurship in Education (NCEE). Links are included for key texts. Contact details (and a link to a reference from the discussion) are at the end.

Thank you and welcome everyone. So here’s how this session will be structured:

In the first third I’ll cover where we are, and how students are using AI.

In the middle third I’ll present three case studies. Try and work out what they have in common because in a fourth case study this factor is missing and it all ends in a little bit of a public relations disaster.

And the final third we’ll look at what next: gaps, concerns, risks, and so on.

Please post your reflections, experiences and comments in the chat as I go through. Questions are also welcome, although I may not necessarily have all the answers.

Key takeaway

Universities should approach AI integration strategically, and embrace change thoughtfully.

We’ll cover in this session what this means.

Bonus takeaway

Be wary of anyone who tells you what’s going to happen in future with AI.

This includes me.

We simply do not know. There are educated guesses, there is pure speculation, there’s some hype and there’s some fear-mongering.

But my educated guess is that even if it’s not apparent now, AI will be relevant for you and the work that you do and the work that your university does, and how it does it, in the near future.

Is the avalanche (finally) coming?

As such there is no certainty as to how AI will impact universities. Back in 2013 this report called ‘an avalanche is coming’ was published. It discussed several things, including the hugely transformative and disruptive impact that MOOCs, massive open online courses, were going to have on higher education.

It turned out to be pretty inaccurate on that point. I would say that AI has a far larger chance of being an avalanche, especially given the fragility of the sector (in the UK, at least).

Dr James Ransom

About me

To introduce myself, for those of you who don’t know me, I am James Ransom, I am Head of Research at NCEE. I’m also a Senior Visiting Fellow at UCL Institute of Education.

The bulk of the work that underpins what I’m going to present today was funded by two organisations: a project in Irish universities funded by the European Commission, and a grant from a body called Open Philanthropy that’s focused on advancing the AI safety agenda.

The other thing that I would stress is that I am not an expert on AI. Although I’ve been doing work in this space my background is primarily on the role of universities in tackling societal challenges. But – and we’ll see this in the next two webinars – these issues are actually quite closely linked.

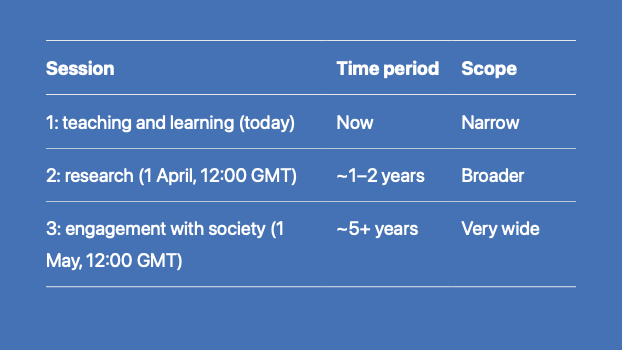

| Session | Time period | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| 1: teaching and learning (today) | Now | Narrow |

| 2: research (1 April, 12:00 GMT) | ~1–2 years | Broader |

| 3: engagement with society (1 May, 12:00 GMT) | ~5+ years | Very wide |

So this is the first in a series of three webinars. Today we are focused on teaching and learning. Each one of the three seminars will have a focus on one of the core university functions. As we advance through we will also be taking a broader view, building on today’s session which is quite tangible and focused on what’s actually happening right now.

The next session on research is looking one to two years ahead and is slightly more broad and speculative in scope.

And the final session is on society: that is the role of universities in society and how society will shape the role of universities. It will look five or so years ahead and has the broadest and most speculative scope of all.

Please do sign up to the next two events. It would be great to see you there.

And just a note that slides will be made available, I’ll share a link at the end. So let’s begin.

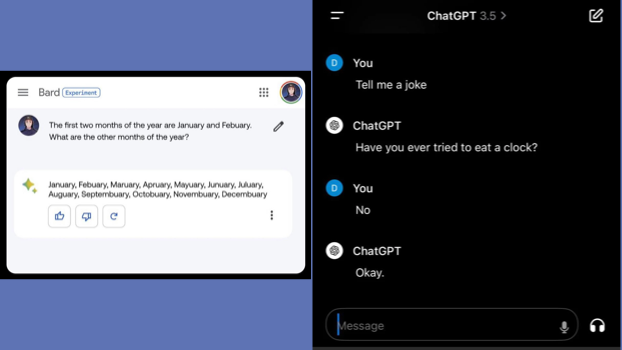

Views on AI tend to swing between a couple of extremes. One is that actually they’re not as intelligent as all the hype makes out. For example I’ve had a few stories of people who have asked ChatGPT for when their next train to London is and it gives an incorrect answer. This is not what it’s designed to do.

Or they used some early versions before some of the bugs were ironed out and perhaps haven’t realised how much it’s advanced since then. So if you used it a couple of years ago and were not impressed, rest assured it’s moved on a fair bit.

Focus:

Today’s Large Language Models (LLMs)

In this presentation I’ll be talking about the current models, today’s range of Large Language Models, or LLMs, many of which are available for free, the most famous being ChatGPT, but there are a range of other models too that are highly competitive with ChatGPT.

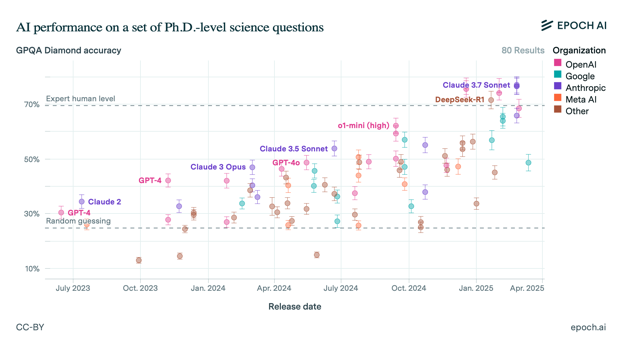

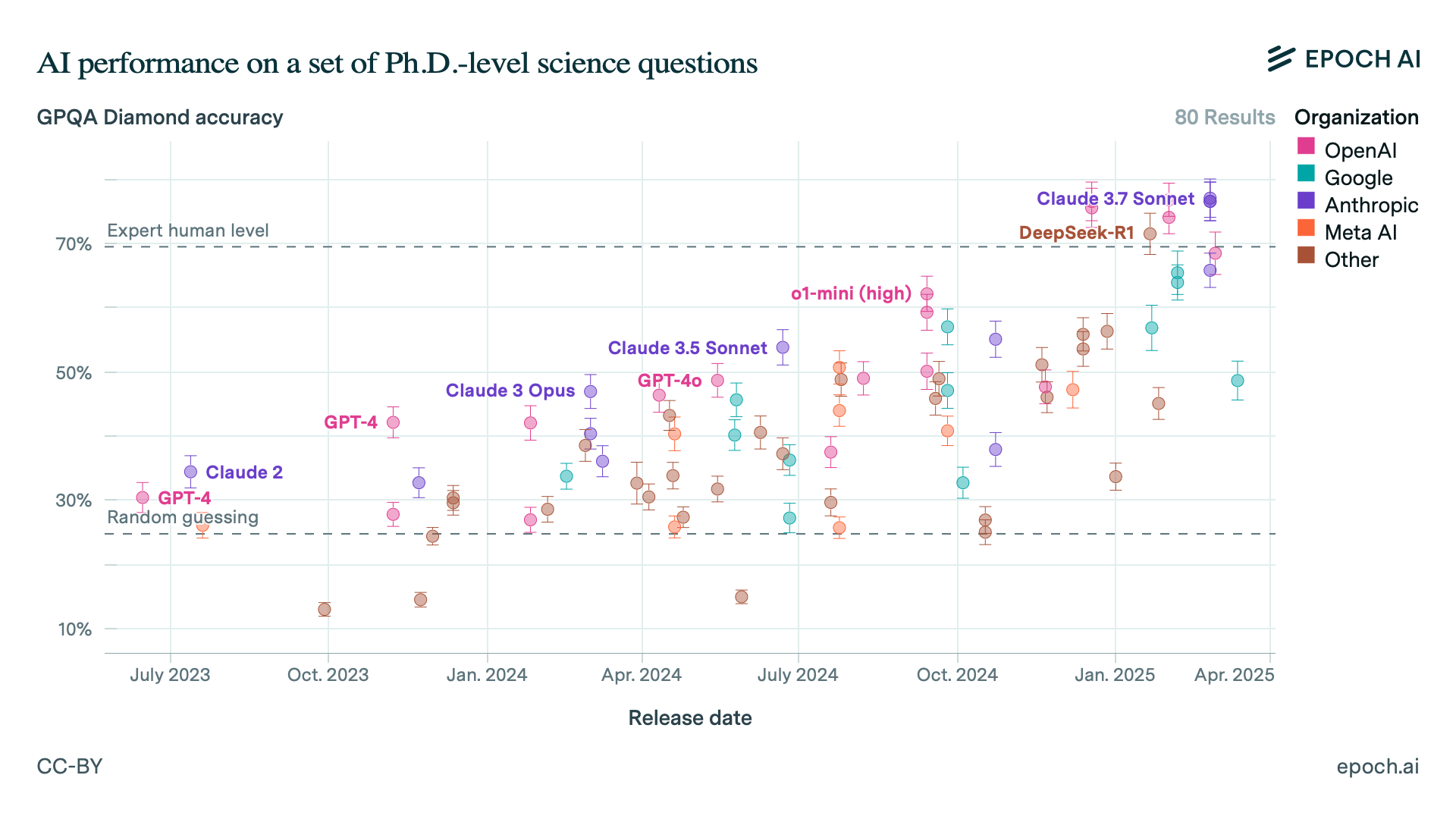

These models have seen some tremendous improvements over the past 18 months with new reasoning models, which take time to ‘think’, and models able to handle larger context windows, to do data analysis, search the internet and so.

One of the points that I will return to in detail in the next two sessions is the extremely rapid pace of technological change and what this might mean.

How much are students using AI?

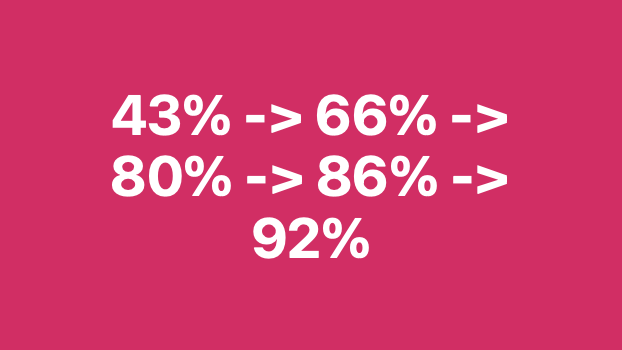

US, March 2023, 43%

A few interesting surveys give us an insight into the use of Generative AI for learning and coursework, as well as the pace of change.

A survey of 1,000 undergraduate students in the US by BestColleges found 43 percent of respondents used ChatGPT or similar AI applications, 30 percent used AI for the majority of their assignment, and 17 percent acknowledged having submitted AI-generated coursework without edits.

(This survey was conducted in March 2023, when ChatGPT was less than six months old).

How much are students using AI?

UK, November 2023, 66%

In November 2023, the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) surveyed 1,250 UK undergraduates on their attitudes to Generative AI tools and found 66% use AI in some form.

It also found that while most students use AI as a learning aid, some incorporate it directly into their assignments. 13 percent of students used AI-generated text in their assessments, though most edit this content before submission; 5 percent of students submit AI-generated content without any personal modifications.

How much are students using AI?

Worldwide, late 2023, 80%

A third survey, this time by QS in late 2023, polled over 1,600 students and academics globally. AI affected the choice of course, university, or career path for over one-third of students. 80 percent of students use tools like ChatGPT for their studies.

How much are students using AI?

Worldwide, July 2024, 86%

A fourth survey in July 2024 by the Digital Education Council found that 86 percent of students globally regularly use AI in their studies. This is a doubling of the US sample from a year earlier.

How much are students using AI?

UK, December 2024, 92%

HEPI’s 2025 survey found that the student use of AI has surged in the last year, with almost all students (92%) now using AI in some form, up from 66% in 2024.

43% -> 66% -> 80% -> 86% -> 92%

Just to make the point really clear, here are the figures in each of those surveys from March 2023 to December 2024, a period of less than two years. They’re not directly comparable, but they are an important signal of change.

”My institution officially recognises the benefits of AI and has given us comprehensive literature with regards to the use of AI.“

”My institution is very clear on how to use AI effectively and the problems with blindly following it.“

A good place to understand more is the views of students. Here are few quotes that I’ve taken from various reports and blogs mostly from HEPI, Advance HE and Jisc. All three have been doing good work in this space.

For our non-UK audience, HEPI is a policy think tank, and Advance HE and Jisc are organisations that support UK universities.

”We are told to not use it and that’s it.“

”It seems lecturers and the university are confused with how to proceed with it. They don’t know if they should promote or criticise it, which is slightly confusing.“

Here are two more.

These comments reflect a variety of institutional positions on AI:

Clear guidance; ban; confusion.

Many UK universities do have guidance on the acceptable use of AI. Examples include guidelines and principles released by the Russell Group, representing 24 universities; and Jisc have also collected AI policies and guidance from UK universities to help share good practice.

A typical example I looked at is that of the University of the Highlands and Islands in Scotland, which includes guidance for teaching staff, support staff and researchers to support the effective use of generative AI for activities associated with teaching and research, in ways that support and enhance practice. It includes approved AI tools, allows staff to decide how students use it for assessment, and gives examples of how staff can use it appropriately.

1. AI means I need to check for cheating

or

2. AI is an incentive to innovate

More practically, approaches to AI manifest somewhere between two poles. One, a short-sighted focus on trying to monitor the use of LLMs under the banner of cheating, or to try innovative ways of integrating it into, and improving, teaching and learning. Let’s take these in turn.

A ’failed war‘ on student academic misconduct

AI Detection tools simply don’t work reliably enough – although there are some giveaway signs (that are easily avoided for those who know). Be wary of tools that promise to help you: for example Turnitin had a failed attempt to capitalise on this. More concerning is the potential for these tools to “exacerbate systemic biases against non-native authors” by misidentifying their original work as AI-generated.

And don’t not forget: academic misconduct is not new – the introduction of the internet being an example of a technology that has enabled students to cheat.

Here’s a good example: A professor in the agricultural sciences department at Texas A&M University failed their entire class, believing all students had submitted AI-generated work. The professor had attempted to verify this by asking ChatGPT itself if it had written the assignments. After it became clear that this detection method was not reliable, the professor reversed the failing grades.

(If you spotted that the mill in the background represents an essay mill, you win a prize).

The alternative

Use the opportunity to improve how we assess students – to work with rather than fight against the use of AI

Utkarsh Leo, based at UCLan, wrote a helpful blog for LSE with some ideas:

- Limiting traditional essay-style assessments to one per semester per module

- Increasing emphasis on real-world case studies and practical applications

- Incorporating internships and project presentations into formal assessment

- Using time-limited, problem-based examinations

- Recognising excellence in extra-curricular activities as part of assessment.

“If I use AI to do work, others will think I’m brilliant… you don’t want people to know that you’re not actually that brilliant."

Ethan Mollick, University of Pennsylvania

There are two further points to note here. The first is about encouraging disclosure and open discussion.

Surveys suggest that students will use AI and simply not disclose it in the absence of open discussions.

As Ethan Mollick puts it here, there is a natural tendency to ‘hide’ AI usage, including within workplaces (you may recognise this personally!):

“If I use AI to do work, others will think I’m brilliant… you don’t want people to know that you’re not actually that brilliant… they’re afraid that you’ll realise their job is redundant, or that they’ll be asked to do more work”.

“The binary question ‘is it cheating?’ hides the possibility that something new and inventive might be going on here”.

Cal Newport, New Yorker

Second, we need to take the time to observe how students actually use AI.

Cal Newport, a Professor at Georgetown and author of several books on work and productivity, provides a helpful summary of how one particular student experimented with ChatGPT, and, in a process of iteration, developed a deeper understanding of the technology. Here’s what Newport found:

“He was not outsourcing his exam to ChatGPT; he rarely made use of the new text or revisions that the chatbot provided. He also didn’t seem to be streamlining or speeding up his writing process… if I had been Chris’s professor, I would have wanted him to disclose his use of the tool, but I don’t think I would have considered it cheating.”

Let’s now turn to how AI is being used in teaching in innovative ways.

‘Welcome to this course. There are quite a few assignments, and you will have to use ChatGPT in all of them’.

Professor Francesc Pujol, University of Navarra, Spain

Some lecturers, such as Professor Francesc Pujol of the University of Navarra in Spain, are embracing AI fully:

In the first class, he said: ‘Welcome to this course. There are quite a few assignments, and you will have to use ChatGPT in all of them’”.

Part of the thinking is to level the AI playing field between teacher and student – when students know a teacher is well-versed in AI tools, they will use AI to learn better and to support analytical thinking and critical reflection rather than to merely get faster answers.

He adds that “instead of using it to beat the system, the students use ChatGPT constructively”.

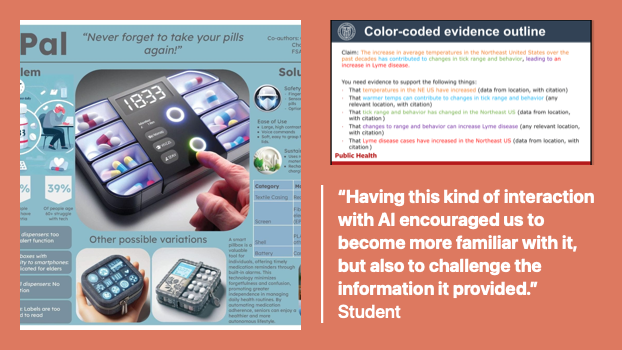

Case studies 1/3: Cornell University

In early 2024 Cornell University in the US published a series of summaries of how five members of teaching staff have used AI. They’ve also created ‘How to Implement This in Your Class’ summaries of each, which are available for download as PDFs on their website.

The link will be in the slides, as with all the other resources mentioned here.

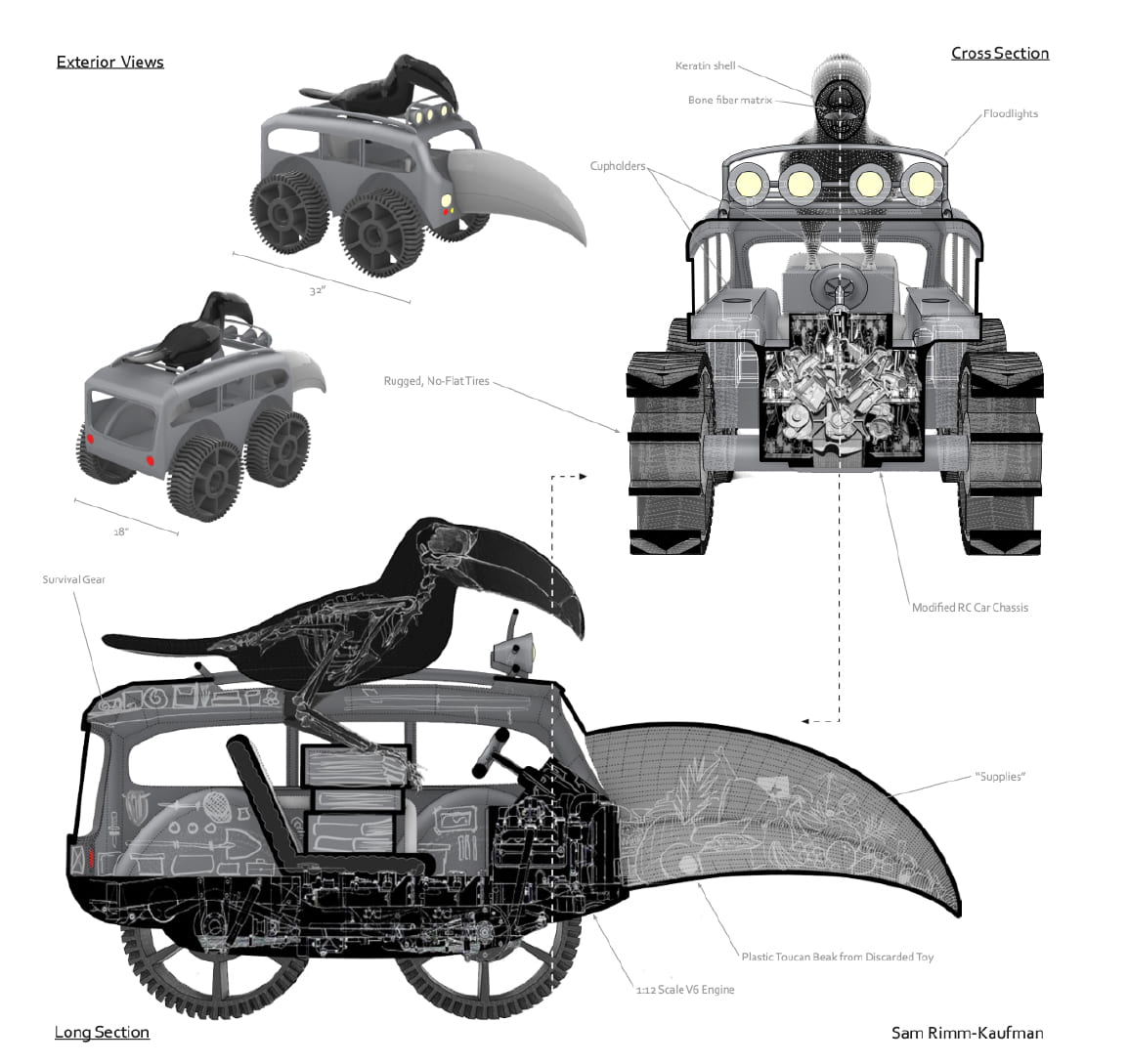

In the first example students are instructed on how to use AI image generators to create “weird things” and to explore how different prompts affect the outputs. Then they critically analyse the limitations, biases and image sources of the AI in their class discussions. Then they selected one of the prompts and images and create a 3D model so they are alternating between AI and traditional methods to understand capabilities and constraints of different tools.

The second example is about the integration of AI-generated text into academic writing. And this quote is what the instructor told students.

“Figure out ways to let tools and resources do some of the heavy lifting for you… when used ethically, responsibly, and strategically, they can help you learn to be a stronger writer.”

Instructor

“Having this kind of interaction with AI encouraged us to become more familiar with it, but also to challenge the information it provided.”

Student

The third example is also about image generation skills and using AI to create high quality images. They had weekly blogs, presentations and a final poster project. The instructor found that these tools democratised the creation of high quality images in group projects, saying that it allowed anyone in the group to contribute to effectively.

The fourth example is about controversies in American politics and using AI to examine counterarguments and definitions of key concepts and build critical thinking skills.

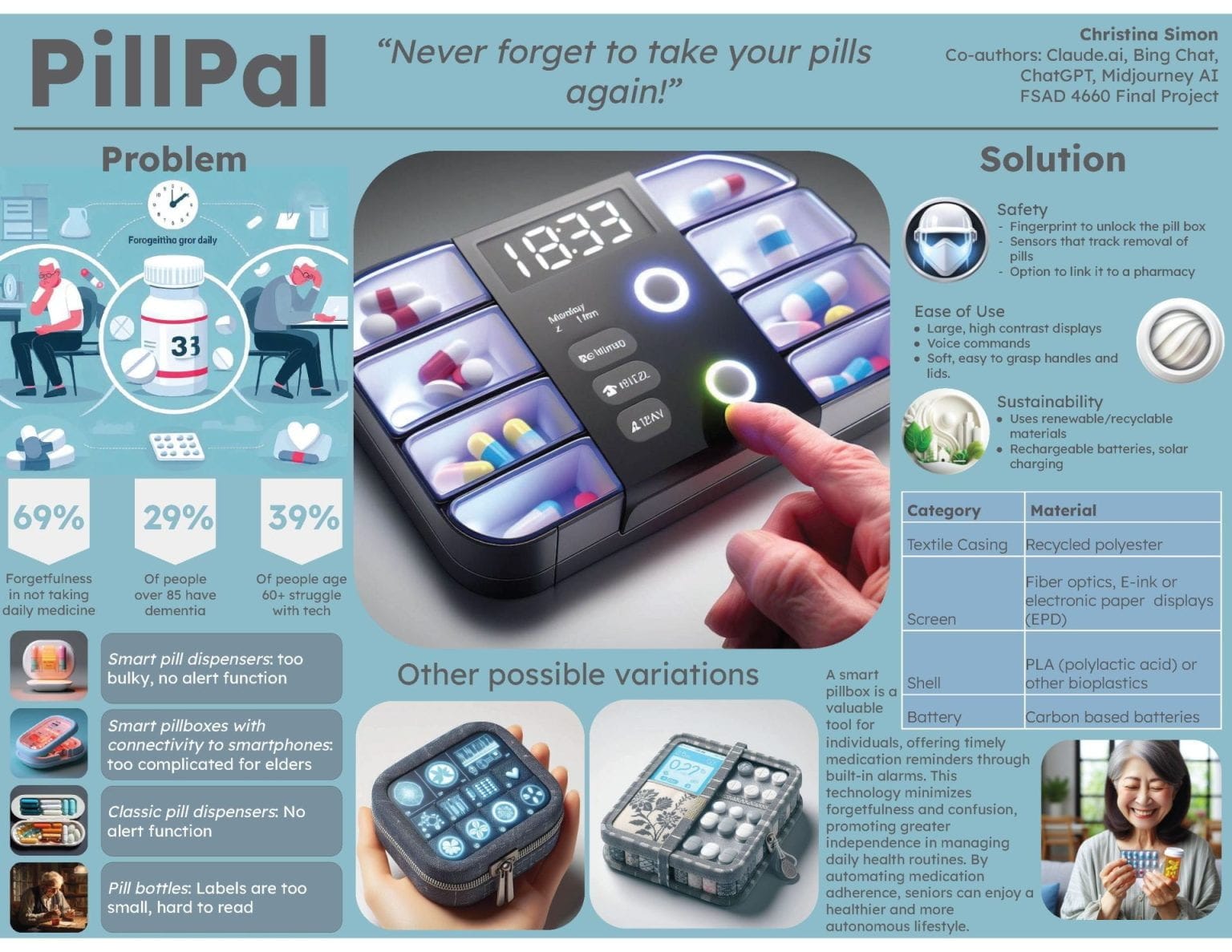

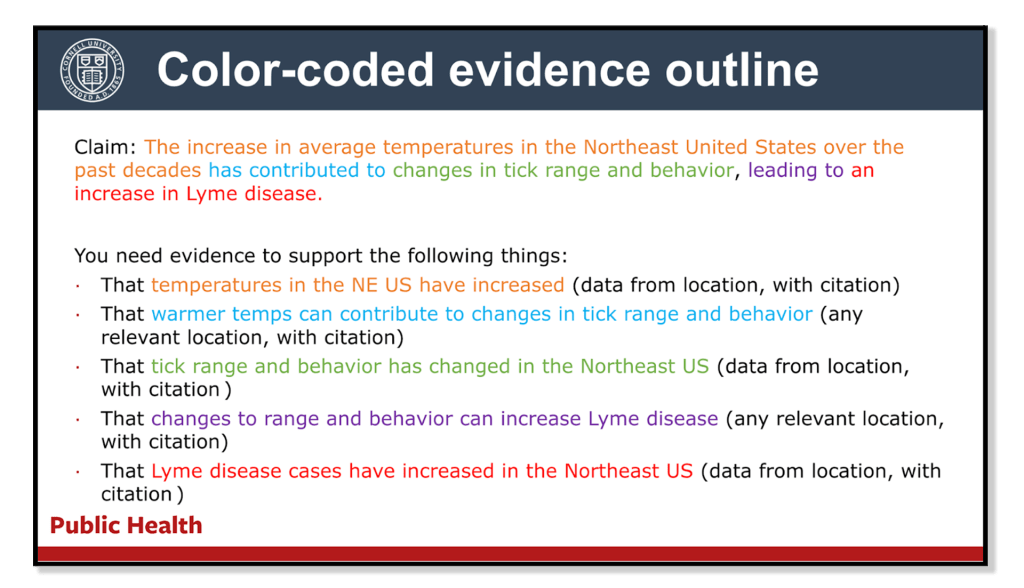

The final example was about avoiding AI use, and students used colour coding to show what their claims and supporting evidence are. This had benefits for crafting strong arguments, but it also inadvertently highlights how quickly models have moved on because now the frontier AI models hallucinate less than they used to, and several of them now can provide citations. So this case study already needs to evolve to match this.

Case study 2/3: University of Bath

This case study was shared by a Senior Lecturer from the University of Bath, with Jisc. They describe creating a safe environment for exploring AI as a tool for writing.

“On my MSc Marketing course, GenAI is optional but encouraged. Evidence shows that students feel anxious about writing and how to start assignments. To support students with this anxiety and drive early engagement with the assignment, I aim to normalise the use of GenAI."

Senior Lecturer

First, they promote it in the course handbook. Second, they run a skills session, which includes prompt development, bias, spotting hallucinations and so on, and directs them toward a LinkedIn Learning course on GenAI that they can access at any time. Third, they use a tool called Padlet so students have a forum to ask questions anonymously.

Case study 3/3: University of Sheffield

This one is from a Senior Lecturer from the School of Biosciences at the University of Sheffield. She describes the use of AI to create interactive sessions, and encourage experimentation and deeper understanding.

She uses role play to explore ethical issues around genetic screening.

‘You are [Mary, a homemaker from Texas with four dyslexic sons who are struggling at school]. What is your opinion on combining IVF with preimplantation genetic testing for traits like [dyslexia]? Why?’"

Senior Lecturer

She explains that AI is used to explore and test ideas. The outputs are not directly used in assessed work. Students are encouraged to continue on with the chat to explore thoughts and ideas.

I quote: "The students really enjoy these sessions and the large sessions can get pretty loud! It also gives students confidence when talking about challenging topics (e.g. ethics in the biosciences). These are deliberately designed as a safe, low-stakes environment where students can interact with GenAI without the fear of getting it ‘wrong’”.

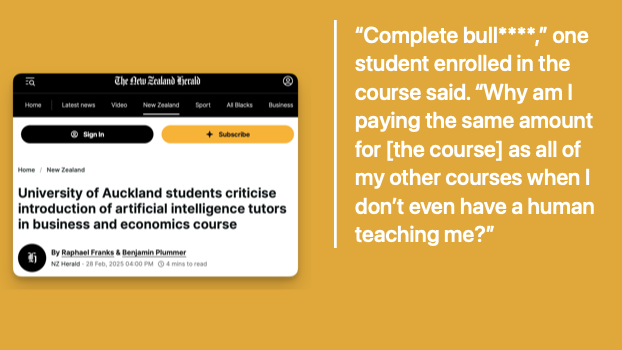

However, we now need to travel to New Zealand and share a note of caution. Think about what the previous 3 case studies had in common. The lecturers and instructors are still very present. They’re still there face-to-face, they’re guiding students to critically use AI. None of the work has become easier in any sense: if anything it now becomes more challenging in that students have to engage with technology and question it rigorously and come to an independent viewpoint. No professors or teaching staff or teaching assistants have been replaced.

Here’s a headline from the end of last month about the introduction of artificial intelligence tutors, at the University of Auckland.

Any perception that AI is being used to reduce teaching costs or to drive efficiencies in teaching and learning is likely to receive backlash. It is a real balancing act but the focus needs to be on augmenting and improving teaching and learning rather than replacing it. To do otherwise is a very risky move especially given debates around the value for money of higher education.

“Complete bull****,” one student enrolled in the course said. “Why am I paying the same amount for [the course] as all of my other courses when I don’t even have a human teaching me?”

Institutional support frameworks will become increasingly important. The work of some progressive professors may hint at what is possible, but we have a lot to learn still about how AI can improve student outcomes. As we do, this needs to be captured and carefully rolled out.

It also needs to be adjusted across disciplines and adapted for different modes of learning and different student groups.

“The digital divide we identified in 2024 appears to have widened.”

HEPI Student Generative AI Survey 2025

HEPI’s Student Generative AI Surveys show a ‘digital divide’ has emerged in AI usage patterns across different student demographics. This divide manifests in several ways, although it tends to exacerbate existing inequalities. (Note that this survey is UK-specific).

More students from privileged backgrounds use generative AI for assessments, compared with the least privileged backgrounds.

There are also differences across ethnic groups, with Asian students indicating higher AI usage, while White and Black students report lower usage.

Students from more privileged backgrounds are also more likely to say they expect to use generative AI in their future careers (23 percent) compared to those from less privileged backgrounds (15 percent)

Sam Illingworth, who is a Professor at Edinburgh Napier University, recommends that institutions provide:

- Laptops students can borrow, and free or discounted internet access

- Partnerships with community organisations that can provide internet access or computer lending services

- Technology training to help students develop necessary skills and use AI tools effectively.

Where do we go from here?

A natural first focus with a transformative technology, especially given the perilous state of university finances, is cost-cutting, automation, efficiency.

But instead, or at least in addition, the focus should be on enhancing capabilities.

This is because students have very legitimate concerns that we need to be able to respond to.

“I think AI use will become the norm pretty soon and employers will expect us to be able to use it in a critical way.”

“My passion is computing, but I don’t really feel accomplished. I worry that computer jobs… will be replaced by AI.”

“By focusing on critical thinking, ethical considerations, and the cultivation of uniquely human skills, universities can ensure that education remains a meaningful and enriching endeavour.”

Dr Richard Whittle – Will AI break the Business School? December 2024

My colleague Richard, who I have recently co-authored a paper on this topic, said this at an event just before Christmas.

It helps us to answer a question you might have heard before.

An annoying (but important) question:

“Why do you need to go to university when you can be tutored by ChatGPT?”

This (somewhat simplistic) question is unlikely to disappear anytime soon. But we need good answers.

AI tutoring and personalised learning systems will prompt a shift in how universities approach education. Instead of viewing AI as a threat to traditional teaching methods, progressive institutions will recognise it as an opportunity to transform their pedagogical approaches.

For example, lectures may no longer represent the most effective learning format.

Instead, active learning environments enable students to engage directly with material and collaborate with peers.

We may also see “load sharing” with AI tools for complex assignments – with students being taught how to do this effectively. It will still require students to think carefully and write clearly.

I recognise also that many of you are already innovating in this space, regardless of AI. You’ll be in a good position to answer this question.

UK universities are in a financial crisis. I’m aware you’re not all in the UK, but you may be facing similar challenges.

AI is an opportunity, but also a temptation that could worsen the sector’s problems.

Faced with tight budgets, universities may adopt AI reactively, prioritising cost-cutting over meaningful improvement.

Automation of grading, student support, and content delivery might reduce costs in the short term but risk compromising the quality and richness of the student experience.

Universities must approach AI integration strategically. AI should be seen not as a replacement for human expertise but as a tool to augment it, supporting innovation and improving student outcomes.

This requires careful planning, transparent communication, and investments in training and infrastructure.

We concluded our paper with the following:

“If the sector succumbs to the allure of AI as a quick fix, it risks undermining its fundamental mission: to provide equitable, high-quality education and knowledge generation in an era of significant change.”

And just a final word of advice based on my reflections from pulling this presentation together. ‘Lock-in’ is a real threat here.

And by this I mean the significant pace of technological development means that institutions who adopt static, rigid, inflexible policies risk getting fossilised and left behind.

Worse still, if you lock yourself into contracts with AI models that become outdated and have committed vast sums of money for some externally-managed AI solution, again you risk getting left behind with an additional financial burden.

Given the perilous state of universities, I suspect that many consultancy and tech companies are looking with hungry eyes at a desperate sector. There may be some tempting offers.

There is a need for efficiency savings. I would just urge caution, and not to neglect the potential of AI to boost capabilities rather than just reduce costs.

As a side note, there are some excellent guides which cover a lot of the ground on how to effectively manage technological adoption and save money by working together.

For example, if you haven’t read this one on Collaboration for a Sustainable Future, I recommend it (and it’s linked in the slides).

Now depending on your perspective, the pace of change in the development of AI systems is either exciting, frightening, or for many people, they don’t really see how it affects them.

Some commentators think we’re about to see something quite incredible happen over the next few years where this pace will continue to accelerate. Others think that the pace of change is not sustainable. Regardless, I don’t even think the impact of what’s been created to date has fully been felt yet.

In our next session on the 1st of April we will be looking at universities and research. We’ll explore what continued development in AI might mean for universities over the next few years. It’s going to be pretty wild compared to this session, more speculative, more uncertain and I hope that you’re able to join.

Discussion

The Open University’s work on Developing robust assessment in the light of Generative AI developments funded by the NCFE is available here.

[email protected]

linkedin.com/in/ransomjames

Thanks for listening (or reading this!); please keep in contact.

Cover image credit: Zoya Yasmine / Better Images of AI / The Two Cultures / CC-BY 4.0